The book under discussion for the month was

Black Elk Speaks: The Complete Edition; The book was written by John G. Neihardt based on sessions with Nicholas Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux (or Lakota).

Hoping a few more folk would show up for the discussion, we began the meeting choosing a book to discuss in February (the lead time allows the Kensington Row Bookship to acquire copies for our members).

We had thought to discuss a book on Catalonia for the session, recognizing that the Kensington Row Bookstore also hosts the Catalan library and reading room of the Fundacio Pauli Bellet, a collection of books in Catalan. Coincidentally, the issue of Catalonian independence is heating up, with a pro-independence government in Barcelona; the Government in Seville is apparently much opposed to that independence. We discovered that Eli (Elesonde Sola-Sole the store owner) and her mother will be in Barcelona on our meeting day, and we therefore postponed the choice of a book on the history of Catalonia until December. Check out these posts on our blog:

We chose a book from a short list (continuing not to focus on books about U.S. history for the next few months):

Member Stew has been reading

From the Ruins of Empire and recommended it highly. It had been recommended to her by the staff of a bookshop she visited on a recent Mediterranean cruise (we commented how useful is access to the curatorial services of the staff of a good bookstore focusing on newly released books).

The Victorian period, viewed in the West as a time of self-confident progress, was experienced by Asians as a catastrophe. As the British gunned down the last heirs to the Mughal Empire, burned down the Summer Palace in Beijing, or humiliated the bankrupt rulers of the Ottoman Empire, it was clear that for Asia to recover a vast intellectual effort would be required.

Released in 2013, this book has already gathered a significant audience and

has been highly rated by nearly 800 readers on Goodreads.

We chose From the Ruins of Empire for our February book.

Joe strongly recommended

Blood and Thunder: The Epic Story of Kit Carson and the Conquest of the American West by Hampton Sides. Allen, who has read the book added his strong endorsement for the book and its author.

In the summer of 1846, the Army of the West marched through Santa Fe, en route to invade and occupy the Western territories claimed by Mexico. Fueled by the new ideology of “Manifest Destiny,” this land grab would lead to a decades-long battle between the United States and the Navajos, the fiercely resistant rulers of a huge swath of mountainous desert wilderness.In Blood and Thunder, Hampton Sides gives us a magnificent history of the American conquest of the West. At the center of this sweeping tale is Kit Carson, the trapper, scout, and soldier whose adventures made him a legend. Sides shows us how this illiterate mountain man understood and respected the Western tribes better than any other American, yet willingly followed orders that would ultimately devastate the Navajo nation. Rich in detail and spanning more than three decades, this is an essential addition to our understanding of how the West was really won.

The book published in 2007

has been widely read and rated by many readers with consistently good ratings. The text runs to nearly 500 pages (of a total of 624) so it is longer that the club's usual limit. We should come back to this book in the future.

Joe also mentioned his conversations with Algonquin tribe members in southern Maryland. There is the

Cedarville Band Of Piscataway Indians who speak an Algonquin language and operate a small museum in southern Maryland.

Black Elk Speaks appears to be a simple book, but it presents the modern reader with complex issues of interpretation and credibility. Black Elk, an Oglala Lakota Indian born during the Civil War meets with John Neihardt on the Pine River Indian Reservation in 1930. He tells the story of his life through an interpreter. Neihardt's daughter takes the story down in shorthand, and Neihardt published a short book telling the story. In spite of the fact that Neihardt was already famous, the book gets only a small audience and all but disappears from American consciousness. Then in the tumultuous 1960s it is published in a new edition and gains a new audience. It becomes controversial. That is the book that the History Book Club met to discuss.

The members of the club came to the book with their own backgrounds. The club has read a number of books about Indians at least tangentially:

Junipero Serra: California's Founding Father;

1493, Uncovering the New World Columbus Created; Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre; Mayflower: a Story of Courage, Community and War; The Pueblo Revolt: the Secret Rebellion that Drove the Spanish out of the Southwest; 1491: New Revelations of the Americas before Columbus. They had seen cowboy and Indians movies and cavalry and Indians movies in which the Indians were always the "bad guys", and later films like

Dances with Wolves and

Little Big Man that were more pro-Indian.

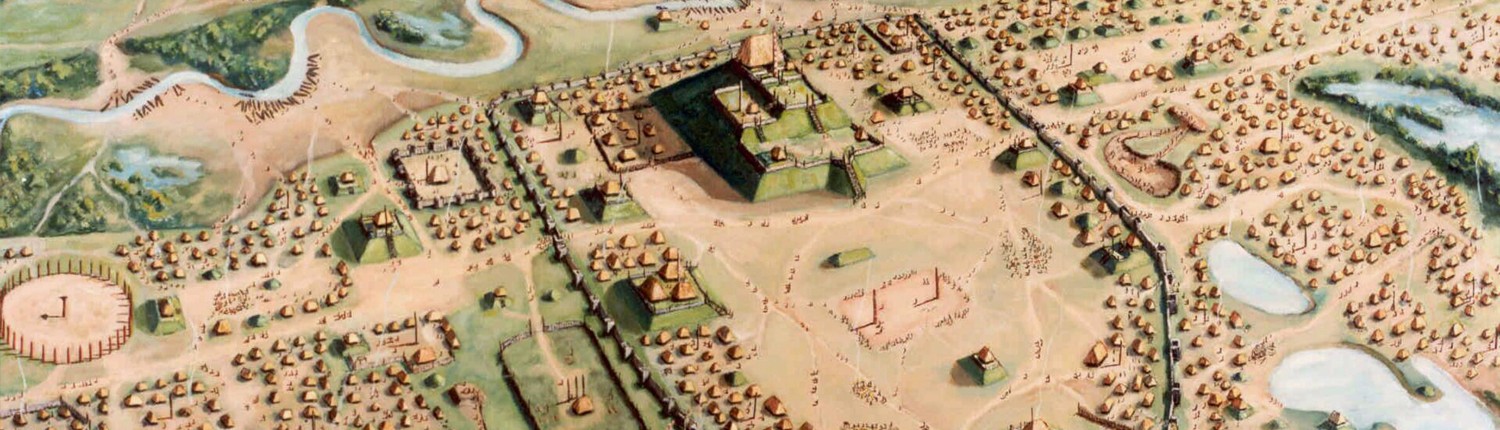

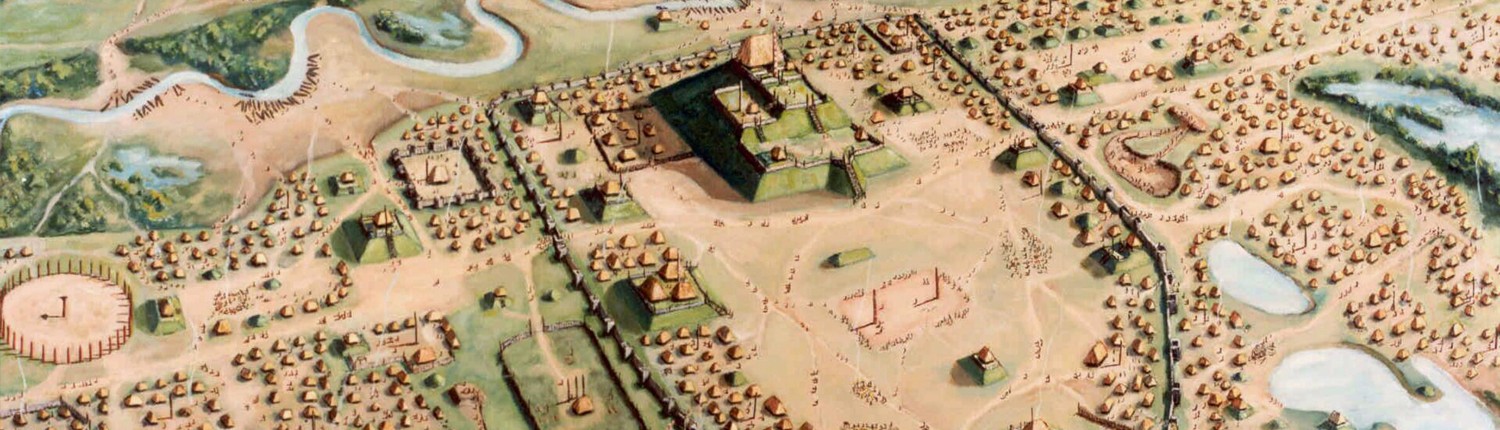

One member mentioned that he had also seen some of the great works of the Indians: Manchu Picchu, Tiwanaku, Teotihuacan, Monte Alba, Chaco Canyon and Kahokia. Mexico City and Cuzco were among the great cities of the world when they were conquered by the

Conquistadores and their Indian allies. He specifically mentioned Cahokia, the main pyramid of which was larger than the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt. The cultural achievements of American Indians are very poorly understood by most Americans.

|

Modern conception of Cahokia with its Great Mound (larger than the Great Pyramid of Egypt and

the thousands of small dwellings of Indian families. Source: Cahokia Mounds State Historical Site |

One member mentioned that she had always wanted to be an Indian when she and her friends played cowboys and Indians; others reported just the opposite. It was mentioned that the scouting movement had tended to favor the Indians, and many scout units were named after the Apaches, the Comanches, and other tribes. These attitudes formed in childhood and the experiences with Indians over lifetimes tended to make our members more (or less) positive toward the Lakota.

Background on Black Elk Speaks by John G. Neihardt

The book was first

published as a thin volume in 1932. It was republished in 1961, 1979, 1988, 2000, 2008; the edition we chose to discuss was published in 2014. This 2014 volume includes as appendices Prefaces to the 1932, 1961, and 1972 edition, as is an introduction by Philip J. Deloria; it also includes appendices by Raymond J. Demalle, Alex N. Petri, and Lauri Utect. Thus this 2014 edition includes a great deal of introductory material and scholarly review material that was not included in the first edition. The first edition, while read by some influential readers, was not sold widely. However, after the 1961 edition was published, the book became quite popular. perhaps due to a rising interest in new age religion as well as an increasing interest by American Indians if their own history (as told by Indians). While controversial, the book has now become an acknowledged classic.

I quote from

the biography of John G. Neihardt provided by Wikipedia:

John Gneisenau Neihardt (January 8, 1881 – November 24, 1973) was an American writer and poet, an amateur historian and ethnographer. Born at the end of the American settlement of the Plains, he became interested in the experiences of those who had been a part of the European-American migration, as well as Indigenous peoples whom they had displaced. He traveled down the Missouri River by open boat, visited with old trappers, became familiar with leaders in a number of Indigenous communities and did extensive research throughout the Plains and Rocky Mountains.

Neihardt wrote to preserve and express elements of the pioneer past in books that range across a broad variety of genres, from travelogues to epic poetry. In 1921 the Nebraska Legislature elected Neihardt as the state's poet laureate, a title he held for fifty-two years until his death.

His most well-known work is Black Elk Speaks (1932), which Neihardt presents as an extended narration of the visions of the Lakota medicine man Black Elk. It was translated into German as Ich Rufe mein Volk (I Call My People) (1953).

Neihardt served as a professor of poetry at the University of Nebraska, and a literary editor in St. Louis, Missouri. He was a poet-in-residence and lecturer at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Missouri from 1948 on.

He was widely honored for his writings.

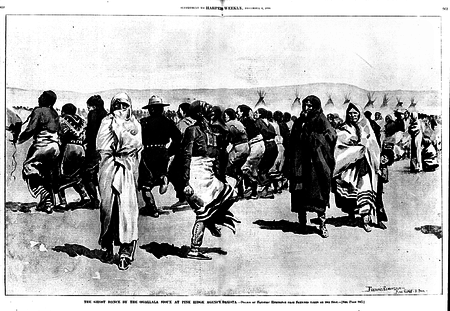

|

Black Elk and Elk of the Oglala Lakota as grass dancers touring with the

Buffalo Bill Wild West Show, London, England, 1887 (source: The Sixth

Grandfather: Black Elk's Teachings Given to John G. Neihardt, edited by

Raymond J. DeMallie, page 259. The men are wearing "sheep and sleigh

bells; otter fur waist and neck pieces; pheasant feather bustles at the waist;

dentalium shell necklaces; and bone hairpipes with colored glass beads....

Photograph collected on Pine Ridge Reservation in 1891 by James Mooney.

Courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution")

via Wikipedia |

Black Elk (December 1863 – August 19, 1950) "was a famous

wičháša wakȟáŋ (medicine man and holy man) of the Oglala Lakota (Sioux). He was

Heyoka and a second cousin of

Crazy Horse."

Black Elk was present at the

massacre at the Little Big Horn (Custer's Last Stand) in 1876, although he would have been only 13 years old. He was also a witness to the

massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890 when he was about 17 years old. Both of these battles have achieved monumental status in western lore. Indeed, he was a boy at the time of many of the battles between Sioux and the U.S. Army.

I quote

from Wikipedia:

In his early 40s in 1904, Black Elk was christened with the first name of Nicholas after becoming Catholic. When other medicine men would speak of him, such as his nephew Fools Crow, they would refer to him both as Black Elk and Nicholas Black Elk.

When Black Elk was nine years old, he was suddenly taken ill and left prone and unresponsive for several days. During this time he had a great vision in which he was visited by the Thunder Beings (Wakinyan), and taken to the Grandfathers — spiritual representatives of the six sacred directions: west, east, north, south, above, and below. These "... spirits were represented as kind and loving, full of years and wisdom, like revered human grandfathers.". When he was seventeen, Black Elk told a medicine man, Black Road, about the vision in detail. Black Road and the other medicine men of the village were "astonished by the greatness of the vision.".........

In 1887, he traveled to England with Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, an experience he described in chapter twenty of Black Elk Speaks . On May 11, 1887, the troop put on a command performance for Queen Victoria, whom they called "Grandmother England." He also described being in the crowd at her Golden Jubilee.

In spring 1888, the Wild West Show set sail for the United States. Black Elk became separated from the group and the ship left without him, stranding him with three other Lakota. They subsequently joined another wild west show and he spent the next year in Germany, France, and Italy. When Buffalo Bill arrived in Paris in May 1889, Black Elk obtained a ticket to return home to Pine Ridge, arriving in autumn of 1889. During his sojourn in Europe, Black Elk was given an "abundant opportunity to study the white man's way of life," and he learned to speak rudimentary English.

For at least a decade, beginning in 1934, Black Elk returned to the work that he had done earlier in life with Buffalo Bill – organizing an Indian show in the Black Hills. Unlike the Wild West shows which were used to glorify Indian warfare, Black Elk's show was used primarily to teach tourists about Lakota culture and traditional sacred rituals – including the Sun Dance.......

Black Elk married his first wife, Katie War Bonnet, in 1892. She became a Catholic, and all three of their children were baptized as Catholic. After her death in 1903, he became a Catholic in 1904, when he was christened with the name of Nicholas and later served as a catechist. He remarried in 1905 to Anna Brings White, a widow with two daughters. Together they had three more children and remained together until her death in 1941.

The Sessions in Which Black Elk told his Story

I quote

from Wikipedia:

In the summer of 1930, as part of his research into the Native American perspective on the Ghost Dance movement, the poet and writer John G. Neihardt, already the Nebraska poet laureate, received the necessary permission from the Bureau of Indian Affairs to go to the Pine Ridge Reservation. Accompanied by his two daughters, he went to meet an Oglala holy man named Black Elk. His intention was to talk to someone who had participated in the Ghost Dance. For the most part, the reservations were not then open to visitors........

Neihardt recounts that Black Elk invited him back for interviews. Flying Hawk served as their translator. (According to Hilda Neihardt and Todd R. Wise in The Black Elk Reader (2000); others say the translation was done by Ben Black Elk, Nicholas Black Elk's son.) Neihardt writes that Black Elk told him of his visions, including one in which he saw himself as a "sixth grandfather", the spiritual representative of the earth and of mankind. Neihardt also states that Black Elk shared some of the Oglala rituals which he had performed as a healer, and that two men developed a close friendship. His daughter Hilda Neihardt says Black Elk adopted her, her sister and their father as relatives, giving each of them Lakota names.

Black Elk then told his story to Neihardt through the interpreter. Older friends of Black Elk who may have had better memories of battles and other events that took place when Black Elk was very young, also spoke from time to time. While the interpreter spoke better English than did Black Elk, apparently his English was not perfect. Hilda Neihardt, then 15, took stenographic notes of what was said, later transcribing them. (These materials are available to researchers in a university library, where John Neihardt deposited them.) Thus Neihardt wrote his version of the monologue from his own memory, from the transcripts produced by his young daughter, from his general knowledge, and from whatever additional materials he may have found through supplementary research. During Black Elk's monologues there were opportunities for questions and answers (again, through the interpreter).

The History Book Club Discussion of Black Elk Speaks

Peter, the club member who originally recommended the book to the club has himself published a number of books on the Indian wars and related subjects. He was not able to attend the meeting, but assured our other members that the information on the battles presented in

Black Elk Speaks is quite accurate.

A member posted this on

the club listserve prior to the meeting:

There are several problems with the book. The first is that Neihardt is the author of the book, I realize that the version selected for the club lists Black Elk also, but that was only been done well after both Black Elk and Neihardt were long dead. That Black Elk was not listed as the, or even an, author has to be taken as a lack of respect for the culture the book describes. Another problem is the claim that Neihardt translated. Black Elk spoke English, though not well, and describing the spiritual aspects of a culture is difficult in its own language, Black Elks son translated. Neihardt worked on improving the translation, which sounds ridiculous to me.

You also fail to mention that Black Elk was a Roman Catholic and an actor in the Wild West Show that toured Europe. Both of those are well documented. Whether Black Elk is a good source of information on Lakota traditions is dubious. I think most of the sources for Black Elk's prominence in the Lakota community are from those promoting their connection to him. The book is used by Indians for guidance because it is the most detailed description available. There were few left to document anything and the culture was effectively destroyed. The Nazis tried to exterminate the Romani, Americans attempted the same with the Indians, neither succeeded but Americans did a better job (or worse depending on your point of view)..

Allen, another member who had recommended the book to the club members, began the discussion mentioning that he had first read

Black Elk Speaks, a slim volume at the time, many years ago. He told us that the book had became very relevant to current events in the 1970s with what has been termed the

Wounded Knee Incident.

The Wounded Knee Incident began on February 27, 1973, when approximately 200 Oglala Lakota and followers of the American Indian Movement (AIM) seized and occupied the town of Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. The protest followed the failure of an effort of the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization (OSCRO) to impeach tribal president Richard Wilson, whom they accused of corruption and abuse of opponents. Additionally, protesters attacked the United States government's failure to fulfill treaties with Indian people and demanded the reopening of treaty negotiations.

Oglala and AIM activists controlled the town for 71 days while the United States Marshals Service, FBI agents, and other law enforcement agencies cordoned off the area. The activists chose the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre for its symbolic value. Both sides were armed and shooting was frequent. A Cherokee and an Oglala Lakota were killed by shootings in April 1973. Ray Robinson, a civil rights activist who joined the protesters, disappeared during the events and is believed to have been murdered. Due to damage to the houses, the small community was not reoccupied until the 1990s.

The occupation attracted wide media coverage, especially after the press accompanied the two U.S. Senators from South Dakota to Wounded Knee. The events electrified American Indians, who were inspired by the sight of their people standing in defiance of the government which had so often failed them. Many Indian supporters traveled to Wounded Knee to join the protest. At the time there was widespread public sympathy for the goals of the occupation, as Americans were becoming more aware of longstanding issues of injustice related to American Indians. Afterward AIM leaders Dennis Banks and Russell Means were indicted on charges related to the events, but their 1974 case was dismissed by the federal court for prosecutorial misconduct, a decision upheld on appeal.

Wilson stayed in office and in 1974 was re-elected amid charges of intimidation, voter fraud, and other abuses. The rate of violence climbed on the reservation as conflict opened between political factions in the following three years; residents accused Wilson's private militia, Guardians of the Oglala Nation (GOONs), for much of it. More than 60 opponents of the tribal government died violently during those years, including Pedro Bissonette, director of the Oglala Sioux Civil Rights Organization (OSCRO).

(Indeed,

many people were indicted and tried for crimes in conjunction with the Wounded Knee Incident.) Allen specifically mentioned

Leonard Peltier who was convicted of murder, and is still in jail; that conviction and his long service in jail was described as especially contentious.

Another member described taking an anthropology course in the mid 1960s, that included not only interviews with Americans, but later interviews with Latin American students at Michigan State University, and ultimately a month living with Tarascan Indians in Mexico (conducting trans-cultural interviews in Spanish).

Editor's Note

The purposes of the participants in the interviews is very important in terms of the credibility of the information reported. Professional anthropologists have been mislead by "informants" who did not want to reveal (sacred) information for religious regions, who hid illegal activity, who did not understand the anthropologists (cross cultural, or poorly expressed) questions, or who simply enjoyed misleading the foreigner. Neihardt was an amateur anthropologist, working from notes his teen age daughter took from a translator.

Neihardt was a writer, more than that a poet. He conducted the sessions with Black Elk in order to obtain material for a book he wished to write. He was writing for a popular audience, and in the 1930s such an audience would have known little about the Lakota people and culture; thus a book would have to tell an (apparently) straight forward tale to get a publisher and audience. Neihardt also reportedly wanted to describe the visions of a noted Sioux visionary and healer to support the belief that a vision he believed he, Neihardt, had received during illness as a child was credible as coming from another level of being. Neihardt apparently credited his own childhood vision as the basis for his choice of career as a poet and writer. The book's text does not question Black Elk's apparent belief in the reality of his own childhood and later visions.

Note that Neihardt could have raised questions about how well a man in his late 60s could actually recall a vision experienced when he was nine years old, or whether recounting that vision subsequently part by part in dance ceremonies might have changed his memory of what he actually experienced. Nor it there mention made that people suffering from high fever often have "fever dreams" that they do not accept as visions from another level of being. Nor does he raise the issue that a man who had been for years a Catholic catechist might have is account of his childhood vision affected by that experience.

The book's text reads is beautifully. Perhaps a high point was the way Neihardt chose to handle the speech of Black Elk and his Sioux colleagues who actually spoke in the Sioux language. How was he to convey the otherness, yet make the text intelligible to his American readers? Neihardt chose to write a prose that was clearly not that which he would choose to represent his own thinking or speech, but which would lend "a flavor of the American Indian". Throughout the original book, Black Elk is clearly the principal narrator (although Neihardt is the credited "author").

The book tells us little about Black Elk's reasons for talking to outsiders, other than Neihardt's acceptance that Black Elk had seen Neihardt's spirit guide (who apparently served as a guarantor of Neihardt's serious purpose and reliability), and that Black Elk wanted to leave a record of his entire vision for posterity -- something he had not previously done. Recalling that Black Elk had served for years in Buffalo Bill's Wild West shows, one might have expected a suggestion that Black Elk liked fame. Perhaps he saw money coming from his tales -- and apparently he was living in real poverty. Indeed, he did start his own Buffalo Bill style show on the reservation focusing on the 19th century lives of the Lakota. Perhaps he was simply a lonely old man, and enjoyed having people to talk to; perhaps he enjoyed the local events related to the story telling (such as the feast and dance that accompanied the sessions and the adoption of the Neihardt's). Indeed, I don't recall even a suggestion that Black Elk may have shaded the story he told to make himself look good.

The account of the Great Vision (Chapter 3) is certainly a high point of the book. The vision is certainly grand, and beautifully told. So too are the later accounts of the ceremonies with entrance processions, dances, songs and scenes acted out by which Sioux people were informed about Black Elk's great vision. For a migrant people leading a simple existence these must have been awesome indeed. We learn that one aspect of the Great Vision was that it taught Black Elk some things that he could use as a healer, and that his activity as a healer came following his sharing of that aspect of the Great Vision in a dance ceremony.

I quote

from Wikipedia:

The Ghost Dance (Caddo: Nanissáanah, also called the Ghost Dance of 1890) was a new religious movement incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. According to the teachings of the Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka (renamed Jack Wilson), proper practice of the dance would reunite the living with spirits of the dead, bring the spirits of the dead to fight on their behalf, make the white colonists leave, and bring peace, prosperity, and unity to native peoples throughout the region.

The basis for the Ghost Dance, the circle dance, is a traditional form that has been used by many Native Americans since prehistoric times, but this new ceremony was first practiced among the Nevada Paiute in 1889. The practice swept throughout much of the Western United States, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As the Ghost Dance spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs.

The Ghost Dance was associated with Wilson's (Wovoka's) prophecy of an end to white expansion while preaching goals of clean living, an honest life, and cross-cultural cooperation by Native Americans.

Practice of the Ghost Dance movement was believed to have contributed to Lakota resistance to assimilation under the Dawes Act. In the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890, U.S. Army forces killed at least 153 Miniconjou and Hunkpapa from the Lakota people. The Sioux variation on the Ghost Dance tended towards millenarianism, an innovation that distinguished the Sioux interpretation from Jack Wilson's original teachings. The Caddo Nation still practices the Ghost Dance today.

It was widely believed among Indian adherents of the Ghost Dance movement that Ghost Shirts, decorated in keeping with the movement's instructions, would protect their wearers from bullets.

The circle dance was apparently a very effective way to move a new cultural practice from tribe to tribe. It may not have been an equally good means to evaluate the credibility of the claims made for that practice. Unfortunately for those wearing the ghost shirts, those shirts did not in fact stop the soldier's bullets.

Black Elk, through Neihardt, provides a clear description of the Sioux experience with the Ghost Shirt movement, a movement that provoked the U.S. troops, and appears to have played an important role in fomenting the massacre at Wounded Knee.

Returning to the Meeting Narrative

John described something he himself experienced as a 15 year old half a century ago. He and a friend had gone fishing for salmon for several days on the mouth of the

Klamath River. The

Klamath Indians hold the fishing rights to the Klamath River, and this was the first time in his life that John met people who identified themselves as Indians. John and his friend camped in a public campgrounds near an elk reserve and near the river. The weather was beautiful, and they simply spread ground sheets, put sleeping bags on top, and slept under the open skies.

One morning, perhaps 3:30 or 4:00 am, John was awakened by his friend who was literally shaking, and who told the following story. The friend had been dozing when he became aware of a large animal entering their camp. He could see the black shadow of the animal against the night sky, and recognized that it must be a full grown elk (which can grow to 800 lbs.) with a full set of antlers. The elk paused on entering the campground, then (according to John's friend) walked to the other side of the camp walking directly over John's sleeping body; it stopped again on the other side of the camp, looked around, and went off into the forest.

John then asked how many of the members present believe that this event was the attachment of a spirit guide to him, a guide that would stay with him for decades eventually leading him to read

Black Elk Speaks and this discussion. Since this question was met by complete silence, he asked why the group seemed to accepting of the story in the book that Black Elk had seen John Neihardt's spirit guide when they first met, and it was that that decided Black Elk to entrust Neidhardt with the task of sharing things with the world that Black Elk himself had kept secret for decades.

A History Book Club member described

Black Elk Speaks as a profoundly sad book.

Black Elk as a young boy lived a life that must have seemed very good. The

Oglala lived in small bands in the Black Hills of South Dakota, dominating their lands. Theirs was a horse culture that traveled light. They were few (only a few thousand) and lived in Tepees. They possessed rifles that made their hunting relatively easy and productive.

They knew their territory well. When they began to have trouble hunting and gathering at one spot, they would move their village to another which they could be confident would feed them all. While they lived in small groups much of the year, they could gather in larger numbers, such as the hunt when the buffalo arrived in the Black Hills.

When young, Black Elk believed he had a mission in life, to lead his people to a still better life. As it turned out, that was not to be.

For years, in an effort to abolish their culture. children of the Lakota had been taken to schools where they were isolated from their families and forbidden to speak the Lakota language. In the 1930s, Black Elk lived in a small "white-man's" house on the Pine Ridge Reservation. The Lakota reservation had (contrary to the terms of treaties) been reduced in size time and again as whites came to the Black Hills, first to mine gold, and then for other reasons. The buffalo were gone, all but extinct. The Lakota culture of Black Elk's boyhood too was all but extinct. Their traditional way of life gone, they tried to survive on skills newly taught to them, but their land was poor and the weather uncertain.

Things are no better now.

According to Wikipedia:

In 2005 in an interview, Cecilia Fire Thunder, the first woman president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, noted the following: "68 percent of the college graduates on the reservation are women. Seventy percent of the jobs are held by women. Over 90 percent of the jobs in our schools are held by women."

As of 2011, population estimates of the reservation range from 28,000 to 40,000. Numerous enrolled members of the tribe live off the reservation.

80% of residents are unemployed (versus 10% of the rest of the country);

49% of the residents live below the Federal poverty level (61% under the age of 18);

Per capita income in Oglala Lakota County is $6,286;

The infant mortality rate is 5 times higher than the national average;

Native American amputation rates due to diabetes is 3 to 4 times higher than the national average;

Death rate due to diabetes is 3 times higher than the national average; and

Life expectancy in 2007 was estimated to be 48 for males and 52 for females

The Lakota history from Black Elk's birth to now has been truly sad.

A Further Comment

Cathy asked "are there any tribes that are successful in today's world?" A quick answer was that some of the small tribes that have gambling casinos located near large cities are doing well economically. Still, it is clear that people living in tribes in the Americas, Africa and Asia as a rule are not doing well. (We failed to note the people in the Arab Emirates have managed to gain control of oil resources while retaining some aspects of tribalism. So too, some business communities highly dependent on trust among members -- such as has been said to exist in the diamond business -- may have aspects of "tribal behavior".)

(We are perhaps drawn back to Angus Deaton's book mentioned above. That book discusses the emergence of a technical and economic system a few centuries ago which have allowed a portion of the world to become much richer, much healthier and much more schooled that the rest of mankind. That felicitous system was based on improved manufacturing technology and the harnessing of new forms of energy which together allowed for efficiency in mass production. This advance was matched by improvements in transportation and the transmission of information. These in turn allowed the cheaper manufactured goods to reach world markets still at low prices -- not just local markets. Raw materials were sourced worldwide, where ever their exploitation was most economical. The new manufacturing and trading elites successfully fought for political power, replacing the old aristocracy that was based on ownership of agricultural land in Europe, America and a few other places that succeeded in jumping on the progress bandwagon. New institutions were created to support manufacturing and globalization of markets, and tribal institutions were left often inadequate to mobilize gains for tribe members. This is a scenario that may apply to the Oglala as well as many other tribal peoples who continued to live as such.)

Editorial comment.

Final Comment

“History is written by the victors.”

― Walter Benjamin

Black Elk Speaks is a rare history written from the point of view of the losers. This book appears to describe Oglala Lakota culture in the late 19th century; that culture was very different that that of mainstream America in the early 21st century. Yet as described by Black Elk though John Niehardt, it is a culture with aspects of beauty now lost. Before we blythely seek to develop other countries, destroying tribal and other cultures in the process, we might stop to wonder what is being lost? Are there better ways to achieve better health and more security for the people of those countries? At least, how ought we to involve the people whose culture is being disrupted in the choices as to about that disruption. Historically, the changes were imposed upon the Oglala Lakota brutally by a people (our American ancestors) sure in their own minds of the superiority of their own culture (which we now see as fatally flawed by racism and prejudice).

The 1932 edition is very controversial, and the 2014 edition with its additional materials helps explain that controversy to the reader. It is important to understand the controversy that surrounds the book -- does it accurately portray Oglala Lakota culture as it purports to do? Is it good history? Is it good Anthropology? Those judgments should vitally affect the conclusions we draw from the book, and how strongly we espouse those conclusions.

The simple book that came from John Niehardt's pen is also quite beautiful and moving. Had it not been so, the book would not have lived so long. It is rewarding to read as a work of literature.