October 8th was the day of the blood moon, and eleven members of the History Book Club met at the

Kensington Row Bookshop to discuss

The Story of a Common Soldier of Army Life in the Civil War 1861-1865 by Leander Stillwell. The book is out of copyright and is available in many forms. For example:

- It is available for Kindle and on paper here.

- Here is the Project Gutenberg free online version of the book.

- Here is a free audio book from the Internet.

The various versions are all computer scanned versions of library copies of the original book. They may contain errors due to the quality of the 84 year old library books or to scanner errors, The Project Gutenberg digital books are proof read by volunteers and tend to have fewer typographical errors; they also have very interesting illustrations that may not be included in other editions

|

| Leander Stillwell in 1863 and later in life |

Leander Stillwell grew up in a frontier farm in western Illinois. He seems to have been a man who loved and understood nature, perhaps typical of the frontiersmen of his time and place. He certainly could find food not only in farmers fields when foraging, but also on a stroll though the forest (as a soldier he seemed often to find opportunities for such lone walks). He was used to guns, having hunted for the pot from the tie he was a young boy. He could also enthuse about the song of a bird 50 years after he heard it.

He joined the 61st Illinois Volunteer Regiment of the Union Army at age 18 in January of 1862. He served throughout the Civil War. A member of our club noted that he had been promoted rapidly to corporal, 4th sergeant, 1st sergeant of his company (a more demanding and responsible position), 2nd lieutenant, and a month later (after the Lee surrendered at Appomattox) 1st lieutenant. After the war he went to law school in New York (with the money that his father had saved for Leander from the army pay that he had sent home) and passed the bar there. He moved to Kansas where he had a long career as a lawyer and judge.

Stillwell began the book at the ago of 72 in 1916 at the request of his son. His original purpose was to leave his family a record of his experience in the war; however during its preparation realized that the memoir might be published and adjusted his writing accordingly. The book was published in 1920.

There was general agreement among the book club members that Stillwell wrote very well. He used a diary he had kept for the latter part of the war as well as an extensive set of letters he had written to his parents during his service; they had saved them and he recovered them late in life. From his comments in the memoirs it is clear that he had read the major works about the war. He also seems to have read a number of the popular works of the 19th century, and quoted them in his memoir. Indeed, he writes about finding a copy of Dickens' Bleak House in 1862 and reading it in barracks. (As was the custom in the 19th century, he reports rereading the book frequently, each time recalling his dreary time in the barracks at its first reading.) We assumed that, as was common with veterans of the Civil War, he periodically met with other veterans and discussed old times. He even met with General Sherman long after the war and had the opportunity to talk with him for several hours about the war (General Sherman was apparently fond of meeting with "his boys" and liked talking to them if they were smart and polite.)

We were impressed by the detail of his memories of the war. One member mentioned that it is not surprising when someone remembers in great detail the most important moments of even a long life. Another suggested that we all are subject to failures of memory, especially as we talk with others and read about the events we experienced. It was also mentioned that people at the time often wrote well, and that Stillwell would probably have written often and carefully in his long legal career.

Service in the Western Theater of the War

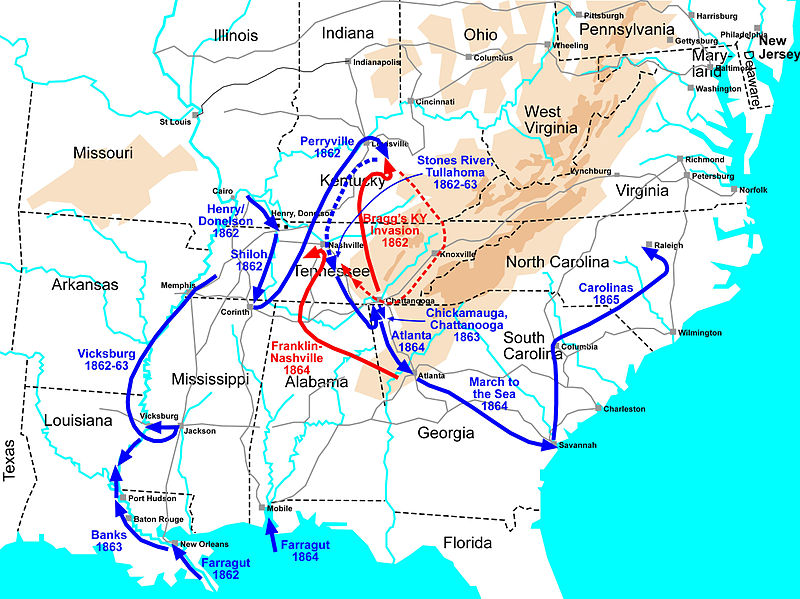

Stillwell and the 62nd Volunteer Regiment served in the western theater of war (see map at the end of this post). They were involved directly

- in the Battle of Shiloh,

- in the siege of Vicksburg guarding the vital railroad supply route for the Union forces, and

- in the taking of Little Rock (by a brilliant maneuver planned by Union General Frederick Steele).

When the battle of Nashville was taking place, Stillwell and his regiment were assigned to nearby Murfreesboro, again protecting a vital railroad; there he was involved in a night running nighttime battle -- Overall's Creek -- in which a large part of his unit was captured. He had hoped to be included in the forces used in Sherman's March to the Sea, but that did not come about. His was the luck of the draw, since an enlisted man has little to say about where he is assigned during a war.

The 62nd Illinois Volunteer Regiment had between 800 and 900 men when it was formed; 37 of them died or were mortally wounded in battle during the war. 187 died of disease. Stillwell himself reports that he was very ill and hospitalized once during his service (although he managed to leave the field hospital early). Of course, the number of men in the regiment varied widely over the course of the war, as some men left when their enlistments were completed or left for other causes, or as reinforcements were received.

There was a discussion as to whether the western theater was a less dangerous place than the eastern theater. The east saw the great battles of Antietam and Gettysburg, Fredericksburg, the Wilderness, Cold Harbor, and the siege of Richmond. One member pointed out that the eastern Union army also went into winter quarters, and fought only occasional battles in the first years of the war; it was only when General Grant took command that battles occurred every week or two in the east. He felt that in fact the experience of the common soldier in the east was probably not too dissimilar to that of Leander Stillwell in the west.

Another member of the club was not convinced and brought our attention to a second book that she had read,

The Story of Aunt Becky's Army-life (Civil War) by

Sarah Palmer. Palmer, in this 1867 book, tells of her three years as a Union Army nurse serving in the eastern theater, and dealing with the almost unimaginable horror of a Civil War battle hospital.

Stillwell was fortunate in not drawing assignments that increased his danger of being captured, wounded or killed, but units in the Western theater saw plenty of action. Indeed, the Union forces in the west played a crucial role in winning the war.

The Enlisted Man's War

A couple of members who had served in the military pointed out that a soldiers life tends to be long periods of relative inaction, some drill and routine work, and very occasional battle. Stillwell may have had fewer battles than many others, but even the soldiers in the eastern theater also spent winters in quarters, and had many more days away from the combat than in combat.

Stillwell's life was hard. He states that:

the great "stand-bys" in the way of the food of the soldiers of the western armies were coffee, sow-belly, Yankee beans, and hardtack.

There were other foods, notably dried peas. The railroads allowed the Union forces in the Civil War to be better fed than the Confederates or the forces in earlier wars, but there were times when food was very scarce. However, there were also times when foraging introduced fresh foods to the diet. Stillwell describes a couple of memorable occasions when he enjoyed the hospitality of a plantation or a Soldiers Home. On the other hand, small groups of soldiers cooked their own food, and when the young men began their service they did not know how to do so and often made themselves sick.

Clothing was grabbed off of stacks of unassorted pants and jackets; the soldiers traded trying to find something that fit. Shoes were better (but they often went barefoot on long marches).

Union troops made long marches on occasion, and did so carrying heavy packs. Roads were often bad or non-existent. The soldiers often slept in tents, and sometimes in the open with a single blanket even in cold weather. Camps were lacking in rudimentary sanitation which is why there was so much sickness.

Stillwell on Soldiers in Battle

We noted that the young men who went off to war in 1862 had no idea of what they were getting into. The first experience of battle was shocking. Stillwell describes standing in line looking for someone to shoot at; his experience as a hunter was that he did not waste ammunition if he was not able to aim at a clear target. An officer yelled at him to shoot as fast and as often as he could into the smoke in the direction that he thought an enemy might be found. A club member recalled Stillwell describing a time when the smoke had cleared and Stillwell and his comrades could the trees riddled by bullets, most of the marks over the heads of where the enemies would have been.

Stillwell noted that that in battle, the work of loading and firing as fast as possible was so all consuming that there was little time for thinking of anything else. He described once firing his weapon and being knocked flat on his back -- he had put a second load in the weapon not noticing that the first had not been discharged. Reports from battles included men firing their weapons with the ram rods still in the barrels. He also mentions that when possible, the soldiers lay down to present as small a target as they could to the enemy.

Stillwell says that he was always deeply afraid going into battle. But he apparently always performed his duty during the battle. (The respect of his peers and his rapid promotions suggest that was true.)

The boys that went to war with Stillwell were quickly turned into men; they lost their naive beliefs about the task that they were about and became serious about the dangers and hardships that they faced, and it showed in their faces.

A member wondered why Stillwell describes the artillery as so ineffectual during the Civil War, usually way off the mark, when artillery caused most battlefield deaths and wounds in the First World War. A response was that between the wars a recoil mechanism had been invented, and was included in World War I artillery pieces. In the Civil War, the recoil of a canon moved the piece some distance; the artillery men would pull it back to approximately the original spot (as marked by the bucket of water used to swab the barrel), but the aim was lost. The artillery pieces in World War I could be aimed with much greater accuracy, and with the recoil controlled could hit the same spot again and again. Given the growth in manufacturing capacity, there was probably a lot more artillery available in World War I as well as more ammunition for the guns to use. It was also mentioned that Napoleon's artillery was more lethal, perhaps because the tactics used in the Napoleonic wars were more vulnerable to artillery fire.

The Union Army

Some 2.3 million men served in the Union army in total, but the peak number serving at any one time was just over one million. Enlistments varied from a few months to the duration of the war. However, the fighting force was always less than the number on the rolls, especially because of the high rates of sickness among the soldiers.

The Centenial Handbook states:

Of the 2.3 million men enlisted in the Union Army, seventy per cent were under 23 years of age. Approximately 100,000 were 16 and an equal number 15. Three hundred lads were 13 or less, and the records show that there were 25 no older than 10 years.

The states had militias during the Civil War which remained under the authority of their governors. A member recalled the story of President Lincoln speaking to three regiments of Ohio militia. They had been on three months enlistments, assigned to help protect Washington not being needed for the defense of Ohio, and were returning home. Lincoln took the opportunity to do some electioneering for the Republicans. But the example illustrates that short term enlistments were still being used late in the war.

We wondered why the soldiers were so disproportionately young. It was suggested that in America's rural economy, the older men who had wives and children might have been needed to work to support their families. A soldier's pay might allow for someone to be hired to replace the soldier on the farm or in the shop, but the soldier's pay was unpredictable and labor was scarce. We noted that Leander Stillwell was also missed on his father's farm when he went off to war, and on furlough he was in farm cloths working the farm on the day after he got back. On the other hand, a three month enlistment in the militia might be possible for a farmer at a time when the farm workload was low.

Civil War Flags

A member, accustomed by years as a teacher to wearing clothes related to the history lesson of the day, came in a light jacket covered with stars and bars, over a tee shirt. She explained that when Lincoln was elected, there were 33 stars on the flag of the USA. Kansas was admitted to the Union in 1861 bringing the number of stars on the flag to 34. West Virginia, which seceded from Virginia during the war, was admitted to the Union as a new state in 1863 -- the 35th star. Nevada was added to the Union at the end of October 1864, bring the 36th star to the flag but most flags were not changed until after the war was over. Our member then removed her jacket with a flourish to reveal the full 35 stars on her tee shirt.

Final Comment

History is usually not written from the point of view of the common man. Leander Stillwell was clearly an impressive person, but he wrote about the Civil War as he had seen it when he was just an enlisted soldier. His was a long, uncomfortable and unhealthy war, punctuated by a few days of terrible danger. He comes across as a man of quiet heroism and stoicism.

The book was chosen as part of a two book deal. It is quite short, while the book chosen for November is longer than our usual choice. This story of a common soldier is worth your reading time.

Here are a

first and

second post on the book by one of our members.