Sunday, April 26, 2015, 11am-4pm

Howard Avenue, Old Town Kensington, MD

|

Apr 20, 2015

Come to the Kensington Celebration of the Day of the Book!

Labels:

Event

Apr 11, 2015

Local Kensington History Event

APRIL 28: Chris and Ed Hyland from the Bantrak Club will have a small train and trolley display and will speak on the Kensington Trolley line. You’ll enjoy the stories related to the trolleys as well as the history of the line. Chris is a long time and quite active member of the History Book Club.

MEETING DETAILS - All are welcome at KHS programs. These are held at the Town Hall, 3710 Mitchell Street, in Kensington, on the ground floor. There will be coffee and cookies at 7:00 p.m. followed by the Program at 7:30, and a brief business meeting.

MEETING DETAILS - All are welcome at KHS programs. These are held at the Town Hall, 3710 Mitchell Street, in Kensington, on the ground floor. There will be coffee and cookies at 7:00 p.m. followed by the Program at 7:30, and a brief business meeting.

Labels:

Event

Apr 10, 2015

Sea of Glory: The History of the U.S. Exploring Expedition

On the evening of Wednesday, April 8th, eleven members of the History Book Club met at the Kensington Row Bookshop. The next day would be the 150th anniversary of Lee's surrender to Grant at the Appomattox Courthouse. That surrender ended Civil War fighting in Virginia and assured the failure of the Confederacy, the survival of the Union and the end of chattel slavery in the United States of America. The following week would mark 150 years since the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Clearly 150 years ago America changed forever.

The club met to discuss Sea of Glory: America's Voyage of Discovery, The U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842 by Nathaliel Philbrick.

The club met to discuss Sea of Glory: America's Voyage of Discovery, The U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838-1842 by Nathaliel Philbrick.

- Here is The New York Times review of the book.

- Here is a long video with Philbrick discussing the expedition.

- Here is the Harvard University Library open collection of online materials on the expedition.

The U.S. Exploring Expedition (U.S. Ex. Ex.) consisted initially of six sailing ships of the U.S. Navy and 346 men, including officers, sailors and seven scientists. One of the ships would disappear en route to a rendezvous, never to be seen again. One would sink in the mouth of the Colombia River. One, the supply ship, would be sent back to the United States early in the voyage. One would be replaced at a mid point. More than 20 crew members died during the four year voyage, and others would be replaced; in total more than 500 men took part in the expedition.

The U.S. Ex. Ex. was led by Charles Wilkes, who was young for the command of such an ambitious undertaking; he was only a Lieutenant, also quite junior in rank for such a command. He was, however, experienced in making naval charts and familiar with the best methods and instruments for the purpose of the day. The other officers were similarly young and of relatively low rank for the responsibility they would bear. The scientists were experts in various descriptive sciences.

Perhaps the most significant purpose of the expedition was to produce charts to help the American whaling fleet reduce its losses from shipwrecks. Thus the U.S. Ex. Ex. was to chart Cape Horn and the southern tip of South America, many Pacific Islands, the coast of Oregon Territory and the Puget Sound. It was also to explore toward the South Pole and if land was encountered (as had been reported by whalers), to chart some of that land. Finally, it was to make scientific collections of plants, animals and artifacts of native cultures, as well as to study those cultures and their languages.

The Science and Map Making

The U.S. Ex. Ex. produced some 240 charts. Members of the club noted that the chart of the Pacific Island of Tarawa produced by the Expedition was still the best available to the U.S. forces as late as the battle for the island in World War II.

A member mentioned that her father had been exempted from regular military service during World War II, and she later learned that because of his marine chart making expertise he had been recruited to make wartime charts of Pacific Islands. Another mentioned a friend, who had been a naval officer surveying charts off the coast of Alaska; the friend said he had loved the job except that the sailors on the ship kept jumping ship -- willing to walk a hundred miles in the wilderness to the nearest town rather than continue the job of surveying that coast. Charting dangerous waters in adverse climates is a tough job even in modern ships.

The U.S. Ex. Ex. brought a huge collection of plants, animals, and artifacts back to the United States. The were exhibited in the Patent Building for some 15 years drawing 100,000 visitors a year. Later those materials were to form a significant portion of the original collection of the Smithsonian. We noted that for the descriptive sciences of botany and zoology, such collections are the basis for taxonomic studies. Often it takes decades before a final taxonomy is agreed upon, and sometimes new species are identified from museum collections very long after the item in question entered the collection. Moreover, good taxonomy is a necessary basis for almost all further work in those sciences.

(Similarly, the collections of artifacts and the dictionaries of native languages made before the native cultures had extensive contacts with the outside world are still invaluable to anthropologists and ethnologists.)

As a result of prodding and lobbying by Charles Wilkes, who himself quickly produced a five volume history of the U.S. Ex. Ex., the Congress continued to fund the scientific work necessary to understand and document the materials collected by the Expedition; thus scientific works based on the Expedition findings came out for years after the ships returned. The earlier Lewis and Clark expedition had failed to follow up its explorations with published science.

Author Philbrick wrote that the U.S. Ex. Ex. led to the creation of

The American Museum of Natural History in New York was not founded until 1869. Charles Peale opened a museum to the public in Philadelphia on July 18, 1786 and his son Rembrandt Peale opened a museum in Baltimore in 1814, but public museums were rare in the early days of the United States. However, private individuals had collections of curiosities and there was considerable public interest in seeing exhibits of materials from other lands and from the frontier.

Evidence was produced by the U.S. Ex. Ex. scientists in support of a proposal by Charles Darwin; he had suggested that as volcanic islands of the Pacific sank, the coral reefs surrounding them grew, thus maintaining the upper levels near the surface of the sea. In this way, after eons of time there would remain only a coral reef enclosing a lagoon and the underwater remains of a volcano. The U.S. Ex. Ex. also produced evidence that volcanic islands occurred in linear chains, with the youngest volcanoes at one end and the oldest and most eroded volcanoes at the other end; this finding was an important piece of evidence leading to the theory of plate tectonic motion.

Perhaps the most telling comment by author Philbrick is that prior to the U.S. Ex. Ex., while some people had done science in the the United States (and the colonies from which it was formed) they were amateurs; it was only after the Expedition that someone could plan to make a career as a professional scientist, earning a living from his scientific work.

Several members of the group were high school teachers, and they asked why the U.S. Ex. Ex. was not part of the High School history curriculum. One answer was that the Expedition had been created under the administration of Andrew Jackson, but returned when John Tyler was in office. The Tyler administration was not willing to give credit to Jackson's initiative. Another reason suggested was that there were courts martial after the voyage which reduced public acclaim for the Expedition's work. Still another reason proposed was the history of anti-intellectualism in American life. (A member took a crack at the question in a blog post after the meeting.)

The Adventure

In this book, author Nathaliel Philbrick chose to emphasize the adventures experienced by the members of the Expedition. There was certainly plenty of adventure in the round the world trip made in sailing ships in the first half of the 19th century.

The U.S. Ex. Ex. was led by Charles Wilkes, who was young for the command of such an ambitious undertaking; he was only a Lieutenant, also quite junior in rank for such a command. He was, however, experienced in making naval charts and familiar with the best methods and instruments for the purpose of the day. The other officers were similarly young and of relatively low rank for the responsibility they would bear. The scientists were experts in various descriptive sciences.

Perhaps the most significant purpose of the expedition was to produce charts to help the American whaling fleet reduce its losses from shipwrecks. Thus the U.S. Ex. Ex. was to chart Cape Horn and the southern tip of South America, many Pacific Islands, the coast of Oregon Territory and the Puget Sound. It was also to explore toward the South Pole and if land was encountered (as had been reported by whalers), to chart some of that land. Finally, it was to make scientific collections of plants, animals and artifacts of native cultures, as well as to study those cultures and their languages.

|

| Source |

The U.S. Ex. Ex. produced some 240 charts. Members of the club noted that the chart of the Pacific Island of Tarawa produced by the Expedition was still the best available to the U.S. forces as late as the battle for the island in World War II.

A member mentioned that her father had been exempted from regular military service during World War II, and she later learned that because of his marine chart making expertise he had been recruited to make wartime charts of Pacific Islands. Another mentioned a friend, who had been a naval officer surveying charts off the coast of Alaska; the friend said he had loved the job except that the sailors on the ship kept jumping ship -- willing to walk a hundred miles in the wilderness to the nearest town rather than continue the job of surveying that coast. Charting dangerous waters in adverse climates is a tough job even in modern ships.

The U.S. Ex. Ex. brought a huge collection of plants, animals, and artifacts back to the United States. The were exhibited in the Patent Building for some 15 years drawing 100,000 visitors a year. Later those materials were to form a significant portion of the original collection of the Smithsonian. We noted that for the descriptive sciences of botany and zoology, such collections are the basis for taxonomic studies. Often it takes decades before a final taxonomy is agreed upon, and sometimes new species are identified from museum collections very long after the item in question entered the collection. Moreover, good taxonomy is a necessary basis for almost all further work in those sciences.

(Similarly, the collections of artifacts and the dictionaries of native languages made before the native cultures had extensive contacts with the outside world are still invaluable to anthropologists and ethnologists.)

As a result of prodding and lobbying by Charles Wilkes, who himself quickly produced a five volume history of the U.S. Ex. Ex., the Congress continued to fund the scientific work necessary to understand and document the materials collected by the Expedition; thus scientific works based on the Expedition findings came out for years after the ships returned. The earlier Lewis and Clark expedition had failed to follow up its explorations with published science.

Author Philbrick wrote that the U.S. Ex. Ex. led to the creation of

- the Smithsonian Institution (as a scientific organization as well as a museum),

- the United States Botanical Garden (to house and display the live plants from the Expedition),

- the United States Hydrographic Office and

- the Naval Observatory.

The American Museum of Natural History in New York was not founded until 1869. Charles Peale opened a museum to the public in Philadelphia on July 18, 1786 and his son Rembrandt Peale opened a museum in Baltimore in 1814, but public museums were rare in the early days of the United States. However, private individuals had collections of curiosities and there was considerable public interest in seeing exhibits of materials from other lands and from the frontier.

Evidence was produced by the U.S. Ex. Ex. scientists in support of a proposal by Charles Darwin; he had suggested that as volcanic islands of the Pacific sank, the coral reefs surrounding them grew, thus maintaining the upper levels near the surface of the sea. In this way, after eons of time there would remain only a coral reef enclosing a lagoon and the underwater remains of a volcano. The U.S. Ex. Ex. also produced evidence that volcanic islands occurred in linear chains, with the youngest volcanoes at one end and the oldest and most eroded volcanoes at the other end; this finding was an important piece of evidence leading to the theory of plate tectonic motion.

Perhaps the most telling comment by author Philbrick is that prior to the U.S. Ex. Ex., while some people had done science in the the United States (and the colonies from which it was formed) they were amateurs; it was only after the Expedition that someone could plan to make a career as a professional scientist, earning a living from his scientific work.

Several members of the group were high school teachers, and they asked why the U.S. Ex. Ex. was not part of the High School history curriculum. One answer was that the Expedition had been created under the administration of Andrew Jackson, but returned when John Tyler was in office. The Tyler administration was not willing to give credit to Jackson's initiative. Another reason suggested was that there were courts martial after the voyage which reduced public acclaim for the Expedition's work. Still another reason proposed was the history of anti-intellectualism in American life. (A member took a crack at the question in a blog post after the meeting.)

|

| The Route of the U.S. Exploring Expedition |

In this book, author Nathaliel Philbrick chose to emphasize the adventures experienced by the members of the Expedition. There was certainly plenty of adventure in the round the world trip made in sailing ships in the first half of the 19th century.

- The U.S. Ex. Ex. not only sailed around Cape Horn, one of the most dangerous places in the world for sailing ships, but stayed there to chart the region. It seems that one ship was lost with all hands in that effort.

- Several of the Expedition's ships then went south, finding a channel through the ice toward the South Pole. The U.S. Ex. Ex. was one of the first if not the first expedition to make sight the Antarctic continent. Philbrick describes how it dealt with iceburgs, storms, dangerous lee shores, and freezing cold to chart 1500 miles of the coast.

- Then after a brief stop at Valparaiso, the Expedition went on to the Fiji Islands where its members charted the dangerous waters, faced angry and warlike natives who were cannibals (yes, they would eat members of the expedition that they killed or captured). A member who had lived in Valparaiso described it as one of the greatest places in the world to live; he would certainly have jumped ship there rather than face what was still before the men on the U.S. Ex. Ex..

- On landing in beautiful Hawaii, the leader of the expedition chose to climb its highest volcano -- over 14,000 feet in altitude. When the locally hired bearers could not continue, he sent back for sailors to carry the heavy equipment and supplies to the top of the mountain (in order for Lieutenant Wilkes to measure the local gravity). That involved a difficult climb over sharp and cutting lava surfaces, which were snow covered at the higher elevations of the volcano. Of course, at the top there was some danger of being killed by gases from the caldera or even by falling into red-hot lava. The crew built huts at the very peak, where they experienced a storm with hurricane force winds and sub freezing temperatures.

- A U.S. Ex. Ex. ship was lost trying to navigate the mouth of the Columbia River. It is one of the most dangerous places in the world were some 2000 ships have been lost -- the equivalent of one per month for more than 150 years. As the ship was breaking up, grounded on shoals, a small boat went out from shore again and again, successfully rescuing the entire crew. Then a small group from the Expedition traveled by land from the mouth of the Columbia River to San Francisco harbor, pioneering in unexplored territory.

We discovered what seemed to be a gender divide in the group over this account of the adventures of the members of the Expedition. Several women member of the group found this discussion excessive if not unnecessary. On the other hand, the men in the group seemed to find the book's combination of history of science and history of an adventurous voyage to be quite interesting and readable. We eventually seemed to settle on an opinion that the author had a right to choose how he would tell the story of the Expedition, but that readers also had a right to avoid the book if they objected to its detailed description of the dangers and hardships faced by its members.

The People and the Interactions

|

| Charles Wilkes |

A considerable portion of the book focuses on Charles Wilkes and his relations with the officers and crew that served under him.Wilkes was an experienced surveyor, who knew about the latest equipment and techniques of his time; he had successfully led a smaller team to chart U.S. coastal waters. However, he lacked the seamanship and the experience in command at sea that would have been expected of someone in command of such an expedition.

Many more senior officers had been considered for the command; some had refused it (perhaps wisely) while others had been dropped from consideration for various reasons. Wilkes was given the command of the Expedition, but denied the rank of Captain that should have gone with it, and denied the title of Commodore that would normally be attached to someone in command of a group of navy ships.

The navy is rank conscious, and the U.S. Ex. Ex. took place many years after the War of 1812. Promotions had been scarce for decades and officers were probably more concerned with rank than they might otherwise have been. It was noted that many of these young officers would later serve through the war with Mexico and the Civil War, when promotions were frequent, and that those officers would reach very high rank. Wilkes, without specific authorization to do so, assumed the uniform of a navy captain and flew the ensign of a commodore for years on this voyage. We assumed that his doing so was noted by his junior officers with disapproval. He also sometimes assigned commands to officers when other, more senior officers were available in the flotilla; that clearly engendered resentments.

We also noted that Wilkes, who had been close to his officers on a previous charting effort and at the start of the U.S. Ex. Ex., seems to have changed behavior radically early in the four year voyage. He became isolated from his officers and his discipline became more harsh. Philbrick suggests he became arbitrary and sometimes unjust in his treatment of subordinates. We noted that in the 1840s it was common for ship's captains to isolate themselves from crew and officers, and that discipline was much harsher than would be accepted today. Books by Patrick O'Brian and the Mutiny on the Bounty Trilogy were cited, as was Rocks and Shoals: Naval Discipline in the Age of Fighting Sails.

Wilkes' orders were secret, which seemed more appropriate for a military expedition than a scientific and technical one. That secrecy was likely to have contributed to the anxiety of the crew. Indeed a member commented on the ward room reaction as each new destination was disclosed, and each seemed even more dangerous than the previous ones. Still, secret orders to captains and commodores were common at the time.

It was noted that long naval voyages in sailing ships were subject to mutinies. Sailors might jump ship in port and never return. Strong disciplinary measures were thought at the time to be necessary. A member noted the danger of judging actions of people in the past by the standards of our time.

Author Philbrick draws heavily on letters home, journals and memoirs of the voyage from the junior officers, and those documents show strong aversion to Wilkes and disagreement with his actions. Philbrick draws especially heavily on the writings of William Reynolds, one of Wilkes most effective critics. Reynolds had been very positive about Wilkes early in the voyage, but turned against him for the latter years of the Expedition; he is described also as a very effective writer. Certainly a group of those officers brought charges against Wilkes and testified against him in Wilkes' court marshal (he was found guilty of only one charge by the senior officers on the panel and continued in the navy rising ultimately to the rank of admiral.)

A confusion was unearthed. Charles Erskine, a crewman in the U.S. Ex. Ex. much after the Expedition published Twenty Years Before The Mast: With The More Thrilling Scenes And Incidents While Circumnavigating The Globe Under The Command Of The Late Admiral Charles Wilkes 1838-1842; that book is quite critical of Wilkes and Philbrick draws on Erskine's writings occasionally. A much more famous book is Two Years Before the Mast by Richard Henry Dana, a cousin of one of the U.S. Ex. Ex. scientists. Several of our members were familiar with the latter book which describes a voyage made at about the same time as the U.S. Ex. Ex., but shorter and to California. Some had apparently mistaken Dana's book for Erkine's book.

Most of the members present seemed to accept author Philbrick's apparent position that Wilkes lacked many of the command skills that would have made for a better shipboard environment. Others pointed out that his skill as a surveyor, his iron will, his dedication and perseverance in the carrying out the tasks set for the Expedition, and (yes) his leadership made the Expedition exceptionally successful. It was suggested by the latter members that while author Philbrick had mined existing sources extensively and considered the evidence carefully, he might be wrong in his conclusions about Wilkes. For the group as a whole, the question of Wilkes leadership remains open.

The Government

The book shows the federal government in the 1830s to be slow and indecisive in the authorization of the U.S. Ex. Ex.. Congress in the 1830s and 1840s seems unwilling to spend money on even important efforts for the promotion of commerce and trade. Politicians in both the Jackson and the Tyler administrations appear petty, and perhaps willing to put political advantage before the more general interests of the country; few seemed to fully appreciate the importance of the U.S. Ex. Ex. nor the magnitude of the task that was given to the Expedition leaders and members.

It was suggested that the 100,000 people a year visiting the U.S. Ex. Ex. exhibit for 15 years helped convince the politicians that funding science might gain them votes. A member commented: "What, ineffective government in the USA! Who would have thought?"

It was suggested that the 100,000 people a year visiting the U.S. Ex. Ex. exhibit for 15 years helped convince the politicians that funding science might gain them votes. A member commented: "What, ineffective government in the USA! Who would have thought?"

The Big Question

A member asked what seemed to be the big question -- why did the government assign so large a task to one big expedition rather than divide the tasks between two smaller expeditions? European governments were in fact mounting more but smaller expeditions at the time -- expeditions with far more limited objectives than those of the U.S. Ex. Ex..

It was suggested that there might have been several reasons for the U.S. government's choice. For example, there might have only been a limited number of officers available with the requisite skills to chart difficult shores, or there might not be enough of the needed equipment (very expensive at the time) to equip two expeditions, or that that was simply not the way the government chose to do it. ("There is the right way, the wrong way, and the navy way!") We failed to adequately explain to ourselves why that choice was made.

It was noted that the class from which leaders were drawn in the United States in 1840 consisted of relatively few but quite distinguished families; Wilkes for example was the nephew of Elizabeth Ann Seton who established the first Catholic school and the first order of nuns in America; Wilkes' nephew, James Renwick, was a successful architect who among other projects designed "the Castle" building of the Smithsonian and the Renwick Gallery.

Final Comments

While the weather was finally nice for a meeting of the club, the turnout for the discussion was smaller than usual; there were reasons -- one person out of town, one or two not feeling well. Still with hundreds of downloads of the summaries of these discussions, we were surprised that a few more people don't come to the meetings.

The discussion was lively and spirited. People were caught up in the issues raised by the book. Perhaps the key issue discussed is why there is relatively little interest in how the modern world of our daily experience came to be. Certainly the history of science and technology is less frequently taught in schools than it might be.

For some of the member of the History Book Club, Sea of Glory was a page turner, combining important aspects of history with an adventure story and vivid descriptions of clashes among people dedicated to their professions and experiencing danger; for others, perhaps not so much.

Here is a blog post on the book by one of our members, written before the meeting.

Labels:

19th century,

American

Mar 26, 2015

Possible Books for June 2015 -- Books of Local Interest

You might be interested in "The 50 ‘essential’ Washington history books" by Mike DeBonis in The Washington Post of 08/19/2011.

You might also be interested in the PBS special on Benjamin Latrobe which is available as a DVD.Grand Avenues: The Story of Pierre Charles L'Enfant, the French Visionary Who Designed Washington, D.C. by Scott W. Berg. 4.2 stars, 352 pages. Book talk by Scott Berg. Here is a review of the book in The Washington Post. In 1791, shortly after the United States won its independence, George Washington personally asked Pierre Charles L’Enfant—a young French artisan turned American revolutionary soldier who gained many friends among the Founding Fathers—to design the new nation's capital. L’Enfant approached this task with unparalleled vigor and passion; however, his imperious and unyielding nature also made him many powerful enemies. After eleven months, Washington reluctantly dismissed L’Enfant from the project. Subsequently, the plan for the city was published under another name, and L’Enfant died long before it was rightfully attributed to him. Filled with incredible characters and passionate human drama, Scott W. Berg’s deft narrative account of this little-explored story in American history is a tribute to the genius of Pierre Charles L'Enfant and the enduring city that is his legacy.

Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, DC by J.D. Dickey 4.6 stars, 320 pages. Book talk by J.D. Dickey. Review in The Washington Post. Washington, DC, gleams with stately columns and neoclassical temples, a pulsing hub of political power and prowess. But for decades it was one of the worst excuses for a capital city the world had ever seen. Before America became a world power in the twentieth century, Washington City was an eyesore at best and a disgrace at worst. Unfilled swamps, filthy canals, and rutted horse trails littered its landscape. Political bosses hired hooligans and thugs to conduct the nation's affairs. Legendary madams entertained clients from all stations of society and politicians of every party. The police served and protected with the aid of bribes and protection money. The city’s turbulent history set a precedent for the dishonesty, corruption, and mismanagement that have led generations to look suspiciously on the various sin--both real and imagined--of Washington politicians. Empire of Mud unearths and untangles the roots of our capital’s story and explores how the city was tainted from the outset, nearly stifled from becoming the proud citadel of the republic that George Washington and Pierre L'Enfant envisioned more than two centuries ago.

Books on Montgomery County History

Montgomery County (MD) (Images of America) by Michael Dwyer. 4.0 stars, 128 pages. Nicknamed the "Gateway to the Nation's Capital," Montgomery County is home to a number of federal agencies and a highly educated and affluent population that has grown increasingly diverse in recent years. Established in 1776, Montgomery County now consists of urban centers like Bethesda and Silver Spring; suburban neighborhoods like Wheaton, Germantown, and Potomac; and scenic rolling farmland interspersed with historic villages, like Brookeville and Barnesville. An additional 50,000 acres of federal, state, and county parkland provide numerous recreational opportunities for its residents.A Grateful Remembrance: The Story of Montgomery County, Maryland 1776-1976 by Ray Eldon MacMaster and Richard K.; Hiebert. unrated, 422 pages. Out of print, but lots of copies available online.

Montgomery County (Then & Now) by Mark Walston, Only one rating, 128 pages. Ranked among the 50 most populous counties in the nation and in the top 10 of the wealthiest, it boasts the most educated workforce in the United States. Through the juxtaposition of old and new photographs, noted author and historian Mark Walston chronicles the progression of county life in all its variety, offering historical insights into how modern Montgomery came to be.

Biographies

My Bondage and My Freedom by Frederick Douglass. 432 pages (300 of the original text itself) 4.6 stars. The book is available in a free online version from Project Gutenberg. Here is a brief text and videos on Douglass from the History Channel TV network. Ex-slave Frederick Douglass was born in Maryland and lived in Washington for many years; his estate at Cedar Hill is now a National Historic Site. This book is his second autobiography-written after ten years of reflection following his legal emancipation in 1846 and his break with his mentor William Lloyd Garrison/ It catapulted Douglass into the international spotlight as the foremost spokesman for American blacks, both freed and slave. Written during his celebrated career as a speaker and newspaper editor, My Bondage and My Freedom reveals the author of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845) grown more mature, forceful, analytical, and complex with a deepened commitment to the fight for equal rights and liberties.

Fortune's Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth by Terry Alford. 464 pages (340 pages of text), 4.3 stars Only hardcover $21.74. Here is Terry Alford discussing the book on C-SPAN's Book TV. Here is the Kirkus Review of the book. In Fortune's Fool, Terry Alford provides the first comprehensive look at the life of an enigmatic figure whose life has been overshadowed by his final, infamous act. Tracing Booth's story from his uncertain childhood in Maryland, characterized by a difficult relationship with his famous actor father, to his successful acting career on stages across the country, Alford offers a nuanced picture of Booth as a public figure, performer, and deeply troubled man.

The Sword & the Pen: A Life of Lew Wallace by Ray E. Boomhower. 5 stars (but only 2 reviewers), 161 pages. From fighting for the cause of freedom during the Civil War to writing of one of the best-selling books of all time, Lew Wallace of Indiana enjoyed a remarkable career that touched the lives of such famous figures in American history as Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Mark Twain, James Garfield, James Whitcomb Riley, and Billy the Kid. Included here mostly because he led the Union Troops in the Battle of Monocacy.

Sickles the Incredible - A Biography of General Daniel Edgar Sickles By W. A. Swanberg. 4.7 stars, 433 pages. The book is out of print but lots of copies available online. Reader reviews are available on Amazon and Goodreads. Sickles was involved in a number of public scandals, most notably the killing of his wife's lover, Philip Barton Key II, son of Francis Scott Key. He was acquitted with the first use of temporary insanity as a legal defense in U.S. history. He was one of the Civil War's most prominent political generals, serving in the Army of the Potomac. His military career ended at the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863, after he insubordinately moved his III Corps to a position where it was virtually destroyed. And those are only a few of the aspects of his life.

Roger B. Taney by Carl Brent Swisher. Unrated (published in 1935, out of print but some copies available online.) 608 pages.

or

Life of Roger Brooke Taney : chief justice of the United States Supreme Court by Bernard Christian Steiner. (published in 1922, scarce on paper) Available free online here. There is a useful reader review of the book on Goodreads.

Taney, a Marylander, is most remembered as the author of the Dred Scott decision of the Supreme Court, of which he was Chief Justice from 1836 to 1864. He also served as Secretary or War and U.S. Attorney General but was the first man to be rejected for confirmation by the Senate when nominated Secretary of the Treasury. He was a central figure in President Jackson's successful effort to close the Bank of the United States. After Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus in parts of Maryland, Taney ruled as Circuit Judge in Ex parte Merryman (1861) that only Congress had the power to take this action.

Not our usual kind of thing, but since F. Scott Fitzgerald is buried in Rockville:

The Crack-Up by F. Scott Fitzgerald. 4.2 stars, 352 pages. A self-portrait of a great writer 's rise and fall, intensely personal and etched with Fitzgerald's signature blend of romance and realism.

or

Beloved Infidel by Sheilah Graham. 4 stars, 338 pages. Autobiography, love story, and literary history, this classic memoir is "the very best portrait of F. Scott Fitzgerald that has yet been put into print". So wrote critic Edmund Wilson about this international best seller in 1959.

Not quite local interest, but here is one more book to consider:

Original Meanings: Politics and Ideas in the Making of the Constitution by Jack N. Rakove (Pulitzer Prize winner) 3.6 stars, 464 pages (365 pages of text). Here is a video of Prof. Rakove's discussion of his book from C-SPAN. Here is the H-Net review of the book. From abortion to same-sex marriage, today's most urgent political debates will hinge on this two-part question: What did the United States Constitution originally mean and who now understands its meaning best? Rakove chronicles the Constitution from inception to ratification and, in doing so, traces its complex weave of ideology and interest, showing how this document has meant different things at different times to different groups of Americans.

Labels:

club business

Mar 14, 2015

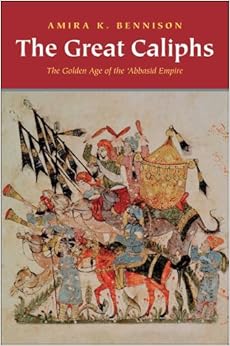

Islam Under the Great Caliphs

A dozen members of the History Book Club met on March 11, 2015 to discuss The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the Abbasid Empire by Amira K. Bennison. It was a balmy evening -- a welcome change after what seemed a long winter. We were hosted again by the Kensington Row Bookshop; the owner was a gracious host as usual.

The date was the anniversary of the first creation of the Army Corps of Engineers in 1794 by the Continental Congress. The anniversary of the first knowledge based enterprise of what would become the United States of America was a fortuitous time to consider the empire that created libraries of works from Greece, Rome and Persia, added to that knowledge base, and passed the heritage of knowledge on to others.

Here is a review of the book, and here author Bennison talks in a video on the cities of the Abbasid empire.

The discussion opened with a member commenting that Bennison's book described an empire founded by Arab Muslims who exploded out of the Arabian peninsula to rule a huge area. The Caliphates from the 7th to the 13th century ruled a huge area, ranging from the Atlantic coasts of North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, into Sub-Saharan Africa, across the Middle East to India, and even down the coast of East Africa. The Caliphates spread Islam where they ruled and they revived trade. In a time when Europe was experiencing the Dark Ages, the Abbasid Empire was translating books from the Byzantine and Sassanid empires, and thus from earlier Greek, Roman, Persian and even Indian sources. These books were copied and distributed, and eventually translated back into Latin and other European languages igniting the Renaissance. We seldom hear about the greatness of Islamic culture at the time, and this book seemed to the member to be a welcome reminder of the accomplishments of the early Muslims/

Another member read an email that had been sent by one who could not attend, as follows:

Although I thought the book had too many names, I thought her coverage of that period of Islam was very interesting. The contributions to western culture were interesting, although not that new. Also, I found the coverage important of the theories of creative and uncreative as intellectual threads in Islam. The importance of different haddit and their role in their culture is also not discussed that much in talking about Islam, just like Talmud and different approaches to it in Judaism is not understood very well. For Moslems it is not just the Koran and for Jews not just the Old Testament. It is not just law in both, but literature, etc.

She (author Bennison) does tread lightly on any persecution of Jews and Christians in the period she covers. Also, the present day nostalgia for this period of power is not addressed and is part of the issues today. An interesting book but not written in a compelling style; sorry to miss the meeting.

|

| Source |

A member chimed in that he had disliked the book as he read the first two of its six chapters, but having read the entire book came to regard it as one of the best books he had ever read. His enthusiasm was due to the breadth of knowledge commanded by its author and shared in this brief book.

Still another member harshly criticized the book. First she found the writing lacking in clarity and elegance, citing examples of torturous sentences and difficult to follow excerpts. Another noted that in this respect the book share a fault found in the writing of many modern professional historians. The book was also criticized for use of many terms drawn from Arabic and unfamiliar to our general audience -- perhaps defined on first appearance, but often unrecognized on a later appearance many pages later. It was suggested that a glossary would have helped.

The Knowledge Survey

An important chapter in the book focused on the translation movement in the Abbasid empire. In this chapter, author Bennison would frequently mention a classical author or an author writing in the period of the Caliphates, and then identify one or more of that author's works. Such references would perhaps be adequate for someone already well acquainted with the authors in question and with their works. However, at least some members of the club found that chapter to be convey little serious knowledge. Yes we learned, that many translations had been done and many books written, including books with new knowledge, but had only the foggiest idea of what was in those books.

The chapter did make the point forcefully that knowledge systems were far more active in the Caliphates than in western Europe at the same time. On the other hand, a member pointed out that the number of writers and scientists a thousand years ago was tiny when compared to the numbers today.

A member mentioned The Book of Roger, described briefly by Bennison. None of the other members was familiar with that title. However, this was a great and famous book by al-Idrisi, a geographer and cartographer -- an Arab who lived in the 12th century. "Roger" was King Roger II of Sicily for whom al-Idrisi created the book. Al-Idrisi is today known as one of the founders of the science of geography.

|

| The Tabula Rogeriana, drawn by al-Idrisi for Roger II of Sicily in 1154 |

We noted that early in the Caliphate period, many of the key positions in government were by necessity occupied by Christians and Zoroastrians who had learned the duties of their positions under the previous regimes. It was questioned whether these folk would need translated versions of the books describing their duties. One response was that they might want copies of the books for their own reference (and to share information with others who did not read the languages of the originals). Later in the Caliphate, when there were more Arabic speakers available for government positions, the translations might have been even more necessary; Bennison also mentions that by that later time, non-Arabss had to be fluent in Arabic to get good jobs in government.

We spent some time talking about the efforts in Spain to translate books from the Caliphate libraries into languages that could be understood in Europe, notably Latin and the Spanish dialects. The club some time ago had read The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain by Maria Rosa Menocal. That book had given a description of how Christians, Jews and Muslims living together in Toledo after it had been reconquered by Christians contributed substantially to that work.

Another criticism was made that the book's focus tended to exclude practical technologies. For example, those involved in the long distance trade must have wanted maps and written documents to which they could refer. Thinking of documents from the Egyptian Genizah (which were a treasure trove of texts from the time of the Caliphates) we noted that even if ships captains sailing the Indian ocean did not need great maps and charts, they did use books with information on the exports available and the imports desired at the ports along their routes.

As another example, we noted that there was an extensive water related technology, from canals to qanats. So too, we know that there was water lifting technology used by the ancient Egyptians (see figure on right) which is still in use, and the Archimedes screw was also available technology from ancient times That is still used today. How were these technologies modified and spread? The book is silent on such topics, perhaps because these were not the topics of the educated men of the time, nor of the school of history to which Amira Bennison belongs.

The Religion

A member asked what did "sunna" mean, a term used in the book occasionally but not redefined each time used. That led to a discussion of the felt need by the early Muslims to supplement the Koran by knowledge of the sayings of Mohammed and the practices of Mohammed and the community of believers he gathered around him (the Hadith and the Sunnah) . Thus there was an effort to record such material in the early days of Islam from people with direct knowledge, or from people to whom it had been conveyed by those who heard it from those who were in contact with Mohammed. Eventually there came to be an effort to define canonical versions of these materials, discarding those which were not trusted. This effort seemed to us similar in some ways to the efforts of the early Jews to define canonical texts of their religion and to those of the early Christians to define a canonical New Testament. (The Book of Peter was mentioned as a purported gospel what was rejected.)

Of course, the content of the Koran was completed by Mohammed, and a member pointed out that extreme care was taken in assuring correctness of copies of the Koran, even when it was copied by hand before the development of the printing press. Faulty copies of the book were (and apparently still are) buried in a respectful manner. It was noted that early manuscripts of the old and new Testaments of the bible have been found with errors crossed out; experts studying these corrections have been better able to understand the biblical texts.

A member questioned "just what is the difference between Sunni and Shiite Islam, and among the various sects within those major branches of Islam. We could not answer that question; indeed, one member noted that he could not answer that question for Christian religion, It was suggested that a standard reference be sought, such as this on Wikipedia.

The Aga Khan, is seen by some 15 million Nizari Ismailis as their imam. He is believed by his followers to be the most recent in a continuous line of religious leaders from Mohammed, via Mohammed's son-in-law (married to Fatima) and nephew. A member noted that one of his friends had gone from working in USAID to working in the Aga Khan Foundation, which deals primarily with members of the Ismaili faith. The member reflected on his friend's comment that it was easier to get things done when he had the authority of the imam believed to be in direct line from Mohammed behind him, than when he worked for USAID.

Prejudice Against Non-Muslims

Under the Caliphates, Muslims were especially favored. However, Jews and Christians as "people of the book" were usually accorded privileges not accorded to animist or followers of other faiths. Christians and Jews were required to make a payment to the state, for which they of course benefited from the protection of the state. (Author Bennison states, however, that this payment was comparable to that required of Muslims, who are required by their faith to make charitable donations, but not required under the Caliphates of other people of the book.)

Slavery was institutionalized under the Caliphates, but Islam forbids making Muslims slaves. Thus under the Caliphates, slaves were obtained from the Christian west, or from the non-Muslim north. It was pointed out that there was also a slave trade with Africa. Some years ago the club chose to read The Sultan's Shadow: One Family's Rule at the Crossroads of East and West by Christiane Bird, which describes the Arab slave trade in East Africa, albeit much after the end of the Caliphates. (This book was so admired, that it was chosen by the club a second time.) Slaves were encouraged to convert to Islam, and many did so over time.

The period discussed in the book (from the middle of the 7th century to the middle of the 13th century) was one of tribalism and continuing warfare between tribes. While Mohammed led in the reduction of tribal warfare in the Arabian peninsula and Islam eventually allowed trade to take place by land and by sea over a huge, pacified area, there were incursions by Turkish and Mongol peoples (who eventually converted to Islam). We noted that at this time, Western Europe also saw prejudice and conflict, noting the Normans, Goths, Vandals and other warlike peoples who exemplified prejudice against other peoples.

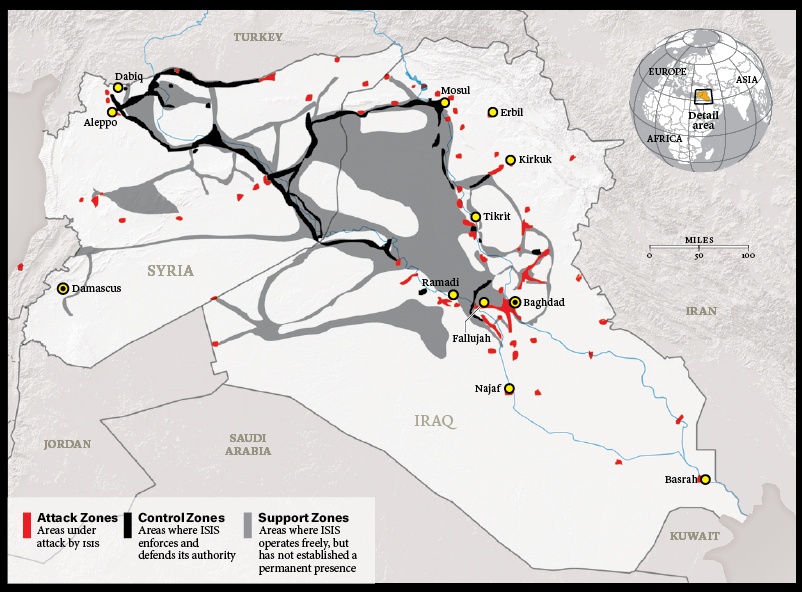

The Islamic State (IS)

Not surprisingly, the Islamic State came up for discussion in out conversation. One member had circulated a recent report by Cole Bunzel published by the Brookings Institution, and another mentioned a recent article in The Atlantic magazine. Still a third member mentioned a recent edition of a serious magazine published by the believers in the Islamic State; she had previously circulated a link to the edition to club members.

Islamic State Territories

|

| Source: "What ISIS Really Wants", Graeme Wood, The Atlantic, March 2015 |

While both emphasize jihad and seek to reestablish "a Caliphate", IS is distinguished from Al Qaeda in that it aspires to be a state, holding land and governing while Al Qaeda is a movement seeking to influence policy through international terrorism with members in many countries . Obviously, of the two, the IS is now the more in the news and now the more visibly successful. The IS is described as based on theological arguments promulgated by its founders. The IS jihad targets both apostates to Islam (as it describes them) and unbelievers; it emphasizes jihad against Shiites. While we did not discuss the history of the IS in any detail, it is important to recognize its claim in 2014 that it was the Caliphate.

Why do people volunteer to fight for (and against) the Islamic State. One member, with long experience as a high school guidance counselor mentioned that many young men he counselled told him of their intent to become soldiers; some people really want to become warriors. Other members added that while there are American soldiers who have volunteered to serve seven or more tours of duty in Afghanistan/Iraq, many others serve one tour, go home and then never go into active combat again. American Sniper, the movie, was mentioned as exemplifying a type of American soldier focused on the technical aspects of combat (perhaps not dissimilar to some of the volunteers for the IS); in response it was pointed out that Chris Kyle, the man portrayed in the film, had volunteered to be a Navy seal and a sniper, and had completed very difficult and very effective training for the function he would fulfill. He must be seen as an exception rather than a typical soldier.

A member mentioned that technology is now available at very low cost to produce quality videos and digital documents and that it is easy and cheap to distribute them online. Not only does the IS do so, but so too does the Donetzk People's Republic. We should not infer from such publications that the publishers are large, strong, well financed organizations. Thus the Islamic State may be less than it appears. A member noted that March 9th and 10th, 2015 were the 70th anniversary of the firebombing of Tokyo by the U.S. air force in World War II; more than 100,000 people were killed, more indeed than by the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima or Nagasaki. The horror of those events put the atrocities of the IS, of which they distribute videos, into perspective.

We diverged into a discussion of the fear that has been generated in the American public by media coverage of admittedly horrible events of violent terrorism, but events that are in the greater scheme of things of no great importance. As a result, the United States sometimes does not focus on more serious problems, such as automobile accidents and gun related deaths, focusing efforts and treasure instead on less dangerous and less pressing problems (e.g. shoe bombers and underwear bombers).

Violent Religions Extremists vs. Muslim Terrorists

One member moved the direction of the discussion by complaining that she did not understand why the members of the IS were seldom described as Muslim terrorists since they clearly were Muslims. There has been a recent effort to focus discussion more on "violent extremists", albeit that many of them profess religious motivation. On the one hand, the vast majority of Muslims clearly are not violent extremists; on the other hand, the relatively recent Rwandan genocide and Srebrenica genocide were committed by violent extremists who were not Muslims. We seemed to agree that violent extremism comes in many forms, and that all forms of violent extremism should be opposed.

We noted that there are many evangelical religions, and extremists professing quite a few of these religions are willing to be violent. Our member recalled as a child being emotionally quite upset by the idea of friends and relatives who she then believed must go to hell since they either refused to join her church (or if members to go to services); another member comments, "but then you grew up". It was noted that Pope Francis (like the leaders of many churches) has emphasized the need for people of different religions to live together in peace.

One member, citing many years working with Muslims in several countries with majority Muslim populations and who had American Muslim friends said that he found the entire discussion of Muslim terrorists at odds with his own experience. He people with whom he had worked tended to be secular in outlook, and were much more interested in promoting peace than in encouraging conflict.

Final Comments

This was quite a lively discussion, one that seemed to involve most of the club members who were present. While there were complaints about the book, it seemed that there was agreement that the author was well informed and that the topic was worthy of our attention. Americans probably should reflect more about that "golden age of Islam" and the dept that we owe however indirectly the contributions made to world heritage under the Abbasid, Umayyad and Fatimad Caliphates.

One of the members has posted comments on the book on his blog:

- The Early Islamic Empire

- The Great Caliphates -- The time of Huge Islamic Empire and Muslim Leadership of World Knowledge

There were several recommendations and announcements of events at the meeting, including:

- The Kensington Day of the Book Festival, Sunday, April 26 11-4pm

- A book talk by Mary Louise Kelly on her novel, The Bullet, at Politics and Prose, March 22, 5 pm Kelly is the niece of a long-time, active History Book Club member; a couple of members who read Ms. Kelly's earlier novel recommended it highly/

- Chris Hyland will give a talk on the railroad and trolley history of Kensington on April 28th at the Kensington City Hall. His model railroad will also be on display. Time 7.00-9.00PM; Refreshments at 7.00 Talk begins at 7.30

- A member recommended the film Of Gods and Men, an award winning French film dealing with a Cistercian Monastery in Algeria in the early 1990s.

Labels:

Africa,

Asia,

Middle East,

Midieval,

Spain

Feb 13, 2015

Virus Hunter: A Biography from American Medical History

On Wednesday evening, about 10 members of the History Book Club met at the Kensington Row Bookshop to discuss Virus Hunter: Thirty Years of Battling Hot Viruses Around the World by C. J. Peters and Mark Olshaker. Dr. Peters is the virus hunter of the title and Mark Olshanker is a professional writer.

The interest of the club was triggered by the Ebola epidemic in West Africa; Dr. Peters is a world expert on that disease, and was the man in charge of the effort to contain an Ebola epidemic in monkeys that occurred in Reston, Virginia in 1989.

We owe special thanks to Eli and Al, the owners of the bookshop. The shop was closed this week, but opened Wednesday evening especially so that the book clubs could meet as regularly scheduled.The meeting began with an unusually long discussion of possible future books to be read and discussed. These are all described with links to obtain more detailed information on the club's blog. There was special interest in two topics:

- California history, since we had not read about that state in the past and its history is quite different than that of other regions of the USA. We were especially interested in Father Junipero Serra, a founding father of the state who is to be formally declared a saint during the visit to the United States by Pope Francis in September. (This will be the first such ceremony ever conducted in the United States, and is likely to be a topic of conversation and debate.)

- The history of the United States as a sea power in the 19th century. It has been suggested that the oceans were an important frontier for Americans before the opening of western lands. Again, this is a topic that the club has not explored in the past, but is one quite important to the nation's commercial, military and scientific history.

Bolivian Hemorrhagic Fever

A member who had been a health planner began this portion of the discussion when he described having been asked to identify a consultant to the USAID mission in Bolivia many years ago. The consultant was to lead an assessment of that country's health sector. The purpose of the assessment was to form the basis for a consideration of a possible health sector development loan. Our member was asked to find a U.S. citizen who was a medical doctor, with a post doctoral public health degree, strong writing and public speaking skills in English, fluent Spanish, who had worked in Bolivia, and who if possible spoke either Aymara or Quechua. After a week of work three qualified candidates were identified. There was an aside at this point on the huge personnel resources of this country, where such requirements can be routinely fulfilled. Dr. Robert Lebow was selected for the job.

What makes that anecdote relevant is that Dr. Lebow also appears importantly in our book. Dr. Lebow had been a Peace Corps physician assigned to Bolivia, and he learned of several cases of hemorrhagic fever that had occurred in Cochabama. Viral hemorrhagic fevers had been of interest to the international health community since they had been discovered in Korea during the Korean War, where they had been a threat to American troops. An Argentinian Hemorrhagic Fever had attracted further notice, especially because it proved highly contagious and highly lethal; one team sent to investigate an outbreak had had every member infected and killed by the disease. Lebow recognized that the outbreak in the middle altitude of Bolivia was unlikely to have come from the same rodent reservoir as that in lowland Argentina. He called for help from the NIH Middle America Research Unit (MARU) in Panama; MARU sent Dr. C. J. Peters to do an epidemiological investigation of the outbreak.

Dr. Peters had exceptional training. An outstanding record as an undergraduate led to medical school at Johns Hopkins University (one of the best in the world), After internship he did a residency in immunology, and then worked as an NIH virologist at the MARU under one of the world's experts for some five years. If you think about it, this was about a decade and a half of higher education and specialized training preparing him for the work he was to do during the rest of a long career.

A Bolivian physician friend of Bob LeBow's had agreed to do an autopsy on one of the victims of the outbreak. Tragically, an accident had occurred during the autopsy, and the man was infected and came down with the disease.

At that point in the discussion, our health planner intervened to describe a visit to a hospital in Cochabama that he had made with an official of the Bolivian Ministry of Health. Several anecdotes served to make it clear to other club members that such a hospital could not adequately care for the man suffering from hemorrhagic fever, nor indeed could it protect its own staff from being infected were they to provide such care.

Lebow and Peters agreed that they would care for the man themselves. That meant rotating 12 hour shifts, each working alone under conditions of considerable personal risk. They did so until the patient died. These two men were physicians who cared deeply for their patients, not just public health officers or scientists, and they had put their own lives at risk. We club members considered them to be heroes.

One of the club members who had read this section of the book late in the evening while in bed reported that she had been so disturbed by the described events that she had needed to put the book down, get up, and watch television for an hour to regain her composure.

Virus Hunters

We discussed the small cadre of highly trained and skilled men who go to the ends of the earth, to the most dangerous of places dealing with the most dangerous diseases to find new threats to mankind and to learn how to deal with them. C. J. Peters is prototypical, but there are others.

A member briefly described the work of Dr, Robert Shope, a Virologist who was on the faculty at Yale for decades and eventually went to a university in Texas. "He helped discover hundreds of viruses, conducting investigations in Malaysia as an Army medical officer and in Brazil for the Rockefeller Foundation. At Yale, he led or participated in investigations of Rift Valley fever, Lassa fever, Venezuelan hemorrhagic fever and other diseases......Dr. Shope also built the World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses, a collection of some 5,000 samples."

A reference center is an important tool, helping virologists identify the viruses that they isolate from human patients or animals. Such collections also help illuminate the genetic relationships among viruses. Discovering that a new virus is genetically related to known viruses can suggest how contagious it may be, how it is transmitted, how lethal it may be, and even how to deal with it.

Dr. Shope was also one of the editors of a major report issued by the National Academies of Science, Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the United States (1992). The Spanish Flu that was associated with World War I was such an emergent disease; it killed 50 million to 100 million people world wide. The HIV/AIDS epidemic is from another emergent virus, and its slow-motion epidemic appears comparably lethal to mankind.

One of the points made in our group is that viruses mutate, and the strains of a virus newly arrived in humans may evolve quickly; it is possible for emergent diseases to become more contagious, more deadly, or both. Such mutation has been one of the threats of the Ebola virus. It is an RNA virus, likely to mutate more often than DNA viruses. The more people that are infected, the more opportunities for the evolution of more dangerous strains of the virus. The current epidemic which for the first time infected more than a handful of people, thus threatened to be the site for evolution of an even worse Ebola disease agent that the current strain.

The point of Emerging Infections was that a global epidemiological surveillance system that was capable of quickly detecting an emerging infection and limiting its spread is of direct value to the United States as well as to all other countries. Some advances have been made in achieving such a system (SARS was mentioned), but it has not yet come near to perfection.

Virus hunters like Drs. Peters and Shope are the first line of defense against emerging viral diseases. There are not many of them, but we were surprised that there were any at all. They are very highly trained, they risk their lives in their work, they travel to the ends of the earth often living in the roughest circumstances, they work in evil locations such as bat caves and infectious disease wards, they must sometimes wear uncomfortable protective gear, and they are paid only modest government salaries. A member who had been a school counselor told us that he had regularly been surprised by students choosing careers that to the outsider seemed most unattractive.

The Reston Ebola Outbreak

|

| Reston Virus |

Ebola broke out in 1989 in a facility being used to quarantine monkeys in Reston Virginai. It was caused by a filovirus similar to the species of Ebola that cause human disease, but apparently several humans who handled monkeys were infected but did not become sick. It was not the same Ebola species that has ravaged African nations. Initially it was thought to be more dangerous to humans than it eventually proved to be and there was great anxiety among those dealing with the disease.

We were struck by the good fortune that the outbreak occurred near Ft. Detrick in Maryland. Dr. Peters was assigned there, and the Army's research facility there had one of the only staffs in the nation capable of dealing with an Ebola virus outbreak. It also had unique physical facilities needed to deal with the outbreak.

One member of our team noted that accidents seem to happen more frequently than one might expect among people handling such dangerous disease agents. A member recalled a (long ago) job as a bartender, noting that cuts were common in that job, even though everyone knew that handling broken glass was a common hazard of the work. Another member, one who had once worked in a military blood bank, added that he too had found accidents there more common than one would expect.

The situation in research involving disease agents is getting safer. Today there are four levels of research laboratories defined, and the U.S. does not fund research unless it is to be conducted in a lab with a sufficient safety rating to assure the security of the research.

In 1989 there was only one level 4 lab in the country, but fortunately it was in Ft. Detrick. That is the level designed to deal with highly contagious, potentially lethal disease agents for which there are no known treatments. That is what is still appropriate for handling the Ebola virus.

We discussed the fact that the thicket of regulations designed to protect the public from health risks also creates barriers to the conduct of the biomedical research that might really protect the public. Virus Hunter is especially good at explaining how this phenomenon worked in the Reston Ebola outbreak. There were different regulations in Virginia and Maryland. There were different federal regulations for use of non-human primates in medical research and for quarantine of imported animals. The federal Center for Disease Control had to be involved as there was a national threat to public health. The Department of Defense had its own regulations. Dr. Peters and his collaborators had to deal with them all and with the officers each employed to enforce its specific regulations.

Some members of our club found it shocking that the ultimate control of the outbreak was achieved by killing all of the hundreds of monkeys in the facility -- healthy as well as sick. This was a terrible job! Monkeys are smart and quickly realized that they were in danger; they are tough and fought for their lives. Many of the cages in the facility (which was a quarantine facility, not a research facility) did not allow immobilization of the monkeys. The people were working in protective suits that were hot, uncomfortable, and limited their mobility. The workers feared that if bitten they might come down with a potential fatal disease. Even disposal of the bodies created problems -- were they potential sources of lethal human infection?

That led us into a discussion of the complexity of rules for the ethical treatment of animals involved in research. For example, there are different rules for treatment of laboratory animals than for livestock, and still different rules for wild animals. The rules for treatment of non-human primates recognize that they are intelligent and much like humans.

That part of the discussion was ended with an unanswerable comment: We thought of a researcher carefully assuring that the cows involved in his research (research funded by the Department of Agriculture, with protocols approved by his university) are treated humanely. Would he then go out and enjoying a steak dinner?

Where Are They Now?

Dr. Robert Lebow continued for many years to consult in the field of international health, but his main interest became a community health service he created in Idaho. He built it into "a $9.3 million a year operation, treating more than 18,000 patients in 10 locations.....(I)n 1998 and 1999 he was (also) president of Physicians for a National Health Program." He published a book, Health Care Meltdown: Confronting the Myths and Fixing our Ailing System. Tragically, he was disabled by an accident riding his bicycle to work in 2003, and died that same year.

Dr. Robert Shope suffered a major pulmonary disease of unknown origin; he died in 2004 as a result of complications from a lung transplant carried out to treat that disease.

Dr. C. J. Peters is still active, and is one of the experts called upon to help deal with the current Ebola epidemic.

Measles

The current outbreak of measles in the United States (after it had been eradicated following the 1971 introduction of the measles-mumps-rubella - MMR - vaccine) led us to a disbelieving discussion. We wondered how highly educated people were denying their children immunization, based apparently on a discredited article published years ago. There has even been a report of a "measles party" -- parents of a child who had contracted measles invited their friends who had children who had not been immunized to bring them so that they too could contract the disease; these parents apparently preferred to immunize their kids by giving them the dangerous disease rather than the safe vaccine. It was pointed out that in 2012, there were some 150,000 deaths from measles in the world, since mass immunization has not been possible in many parts of Asia and Africa.

A member pointed out that German measles (also known as rubella) was a real danger to pregnant women, causing many unwanted abortions prior to the general availability of rubella immunization.

Another member reported having contracted mumps as an adult prior to the availability of the MMR vaccine. He wound up hospitalized with a dangerous complication. Mumps too is a dangerous disease.

That member who had suffered an attack of shingles strongly recommend adult immunization against shingles. It was noted that the vaccine does not offer 100 percent protection and that shingles may recur, but reduction of the likelihood of an attack is still worthwhile. However, another member mentioned that she had a chronic medical condition that precluded her taking the vaccine.

The bottom line of this portion of the discussion was that while vaccines are generally safe, some vaccines are dangerous for some people. While vaccines are one of the most important advances in public health, one should always consult with one's physician before being vaccinated. One should not follow medical advice about so important a matter from untrained people.

Ebola in West Africa

We concluded the discussion with a review of the current information about the Ebola epidemic in three African countries -- Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. There have been nearly 23,000 reported cases, of which nearly 13,000 have been confirmed by laboratory tests. There have been more than 9000 deaths.

While at one time there were 1000 or more new cases being reported a week, in January 100 cases or less were being reported per week. That reduction has led to a change in the response strategy. Now emphasis must be placed on maintaining the effort, identifying every contact, quarantining contacts when possible, isolating the infected and eliminating every last case.

We discussed why the incidence had fallen off. In part this was because community behavior had changed, and people were avoiding the contacts that earlier had led to the high contagion rate. In part the change in behavior was due to the impact of public health messages, in part to people spontaneously choosing to avoid Ebola victims, and in part it was due to the officials sending burial teams in protective gear to bury the Ebola dead rather than leaving that task to family and community members.

During this epidemic, it was learned that people sick with Ebola hemorrhagic fever were more likely to infect others later rather than earlier in the course of the disease. Early case identification and hospitalization therefore seems to have had a significant benefit in reducing the spread of the disease.

We noted that people who recovered from Ebola had gained an immunity, and young recovered people were playing an important role in caring for the many Ebola orphans -- children who are sometimes shunned by relatives who might otherwise care for them but fear that they may still carry the disease.

The U.S. troops who had played an important role in building facilities to help the countries deal with the epidemic are now largely back in the United States. The USA is still supporting some 10,000 people in West Africa working to end the epidemic, most of them Africans. There are more than 200 U.S. Center for Disease Control staff there contributing to the epidemiological efforts.

The world still has few remedies to help a patient survive Ebola hemorrhagic fever. A member brought in an article from the Washington Post that described the difficulties of testing new treatments that have emerged for the disease; there is only a waning numbers of patients on whom to do the tests. She also brought in an article from the same source that described three potential vaccines, two of which have entered testing; the completion of those trials is also questioned.

Final Comments

Looking back, the discussion was wide ranging, focusing on topic about which we would like to know more. These topics ranged from the history of the parts of the United States with Hispanic backgrounds, to the role of Americans at sea, to the fall of the Ottoman Empire and how its division influences the region today, and indeed to medical history.

The Book Club has not focused on American medical history in any depth in the past, and this week we focused on one story from that history, especially as seen through the biography of one man, C. J. Peters. It is the story of the scientifically trained experts who contribute to our knowledge of infectious diseases.

Many historians of medicine believe that a century ago a visit to a doctor was more likely to result in harm to the patient than medical benefit. That century has seen unprecedented advances in medicine and a corresponding dramatic increase in life expectancy in the USA. Much of the improvement has been achieved through the prevention and treatment of communicable diseases -- notably the development of vaccines, antibiotics and antivirals (as well as other drugs treat some communicable diseases).

On the other hand, the 20th century saw the Spanish flu and HIV/AIDS pandemics and many epidemics. Moreover, the benefits of modern medicine have still not fully penetrated to the ends of the earth. Experts believe that new disease agents will emerge, probably in these under-served areas, with the potential to cause new pandemics.

The virus hunters have been in the vanguard of the public health movements. They remain the front line defense against emerging viral diseases. They are a special breed, often heroic. The History Book Club members present enjoyed beginning to learn about these heroes and their work.

Below are President Obama's recent speech on American leadership in the Ebola response (which was distributed via the club blog) and two posts related to the book by one of our members on his own blog.

On the other hand, the 20th century saw the Spanish flu and HIV/AIDS pandemics and many epidemics. Moreover, the benefits of modern medicine have still not fully penetrated to the ends of the earth. Experts believe that new disease agents will emerge, probably in these under-served areas, with the potential to cause new pandemics.

The virus hunters have been in the vanguard of the public health movements. They remain the front line defense against emerging viral diseases. They are a special breed, often heroic. The History Book Club members present enjoyed beginning to learn about these heroes and their work.

Below are President Obama's recent speech on American leadership in the Ebola response (which was distributed via the club blog) and two posts related to the book by one of our members on his own blog.

Previous blog posts:

Labels:

20th century,

American

Jan 30, 2015

Possible Books for April 2015

|

| Woman reading (c.1912). Karl Alexander Wilke |

"And she is the readerwho browses the shelfand looks for new worldsbut finds herself.”Laura Purdie Salas

Perhaps it is time for the club again to read some North American History. Here are some books that you might consider:

Junipero Serra: California's Founding Father by Steven W. Hackel. 352 pages, 4.1 stars. Father Serra has been called the most important man in California history. He established a chain of missions through the state three centuries ago that completely changed the lives of its Indians. The Spanish heritage is marked in place names: San Diego, Nuestra Senora de los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Francico. Steven W. Hackel’s groundbreaking biography is the first to remove Serra from the realm of polemic and place him within the currents of history. Here is an article on Serra that mentions the book. Here is a brief article by author Hackel on Father Serra. Here is a video news report triggered by the Pope's recent announcement that Father Serra is to be recognized as a saint; Hackel is included as an expert. Selected for May 2015

Bridges

Golden Gate: The Life and Times of America's Greatest Bridge by Kevin Starr. 224 pages, 3.8 stars. Kevin’s Starr’s Golden Gate is a brilliant and passionate telling of the history of the bridge itself, and a recounting of the rich and peculiar history of the California experience. The Golden Gate is a grand public work, a symbol and a very real bridge, a magnet for both postcard photographs and suicides. In this compact but comprehensive narrative, Starr unfolds the hidden-in-plain sight meaning of the Golden Gate, putting it in its place among classic works of art. Here is the New York Times review of the book. Here is a video with author Starr talking about the bridge.

The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge by Guy Talese. 208 pages, 4 stars. Towards the end of 1964, the Verrazano Narrows Bridge—linking the New York City boroughs of Brooklyn and Staten Island with New Jersey—was completed. It remains an engineering marvel almost forty years later—at 13,700 feet (more than two and a half miles), it is still the longest suspension bridge in the United States and the sixth longest in the world. This is a reissue of Talese's 50 year old book on the construction of the bridge. Here is a review of the book. Here is a long video interview of the author about the book.

Americans on the Oceans